After the closure of Wigan Casino in 1981, there was a period the older generation referred to as ‘the dark ages.’ The all-nighter scene thrived in this post-wigan period, with a plethora of all-nighters and record discoveries. Mixing with the older crowd was a new generation of soulies, scooterists and mods. New venues such as Stafford’s Top of the World, and Leicester’s Oddfellows, made the Midlands the new centrality for the soul all-nighter scene.

When people think of the soul scene, the classic venues up north often come to mind. This is because Blues & Soul presented the scene with this angle. But the Midlands has always had a rich all-nighter scene, with venues in Northampton predating 1963. The scene thrived during the late 60s and early 70s, attracting soulies dressed in a skinhead style fashion at venues such as The George, Nags Head, Shades and Tin Cat.

It wasn’t harmonious during the 1980s. There was an on-going musical divide between some of the people who only liked modern soul or sixties that had begun in the mid-70s. In the 80s, a slew of sixties new discoveries were being played (coined sixties newies). The DJs who pushed these records were dubbed the Sixties Mafia. Other DJs played contemporary 80s soul releases. A product of this was one of the most diverse and innovative music catalogues in the scene’s history. The music at these nighters has been described as “taking the best of Wigan and building on it.”

Amongst other issues was the snobbery toward the newer generation. Some of the older crowd turned their noses up at the younger crowd. A few would call Stafford a soulies nighter and Leicester a “scooterist” nighter because it attracted a younger demographic.

Sian (pictured to the right) was accused of coming onto the soul scene on the coat tails of Quadrophenia (probably the coat tails of a fishtail parka). She’d never even seen the film! Her entrance onto the scene highlights the crossover between these various scenes over the period.

Listening to records at her friend Rob’s house, she discovered the soul sound and was invited to her first nighter. Rob also used to go to the scooter rallies with her cousin Ges. Rob’s older brother went to Wigan Casino. What you see here is a generational difference within the access grass roots. For the older generation it was in youth clubs, for the newcomers it was this alongside the Mod revival of the late 1970s.

Black Echoes - finding out where and when

Before the mobile phones and the internet, the main way to find out about musical events was through magazines. For gigs, NME or Sounds was your go to. But for the all-nighter crowd, Black Echoes was your periodical of choice. Black Echoes (founded 1976) was published weekly and advertised all the upcoming soul events inside the back page.

weekenders that weren’t really weekenders

For the dedicated soulie, each weekend was a four-day venture. The weekend would start on a Thursday at a soul night (ending at 2AM), and All-Nighter Friday (12-8am), All-Nighter Saturday (12-8am) and an All-Dayer to finish the weekend on a Sunday. In-between these events, people would often meet up afterward at service stations.

Transport varied for many, some jumped in cars together (sometimes a tight squeeze of 8 people), drove scooters or hopped the train. People would often find each other lost on dark country lanes and help each other get to the venues. With limitations in communication in technology, sometimes people would turn up to an event to find out it had been cancelled.

Many would bring all-nighter bags with multiple changes of clothing. This was mainly due to sweating through your clothes whilst dancing or attending multiple events over the weekend without going home.

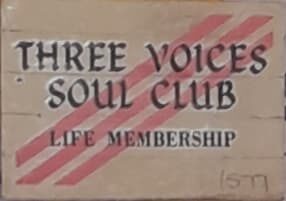

To gain entry to all-nighters, you had to have a membership to the club. You could also use memberships from another club to get into other all-nighters. This was primarily designed to keep out troublemakers. Local pissheads would sometimes try and get into the all-nighter or start trouble with those in the queues.

All-nighters were never violent, unlike your typical night up town. But when others did try and start trouble, punters were more than willing to defend themselves. A gang of psychobillies once tried to start trouble with people in the queue at Oddfellows. This was met with a retaliation from the Leicester football hooligan crowd who quickly ran them off.

Top of the World, Stafford All-nighter (April 1982-Feburary 1986)

Top of the World all-nighter opened its doors on April 1982. The event would start at midnight (as did many other nighters) and end at 8am. Punters would have to queue on the stairs leading up to the top room. the soul night upstairs that opened at 12 O’clock. Down below, the main room served as a nightclub that shut at 2am. After 2am, the room downstairs opened as the main room.

Promoted by Dave Thorley, the original membership card was Top Dog soul club. On August 24th, 1985, Top Dog became Three Voices. The Three Voices was founded by Chris King, Dave Thorley and Steve Croft to stop the clashing of all-nighters and share some of the running costs. Stafford was still a Top Dog promotion, but they went under the banner Three Voices.

A self-consciousness to avoid all-nighter clashes has always been important. But some did clash to cause trouble. This is because too many events can risk musical oversaturation, financial strains on promoters and overall diminished quality from punters to DJs.

What distinguished Stafford from others is its reversal of the function the main room and side room. Typically, all-nighters designate the main room for Oldies (already established records) and the side room for new releases and discoveries. However, Stafford turned this on its head with the main room being the progressive room.

New discoveries would be played each week, to a point where the rate of new plays was relentless in the main room. These records would often be played 4/5 times a night between sets to get dancers acclimatised to the new sounds. Something that would be highly frowned upon on today’s scene. If no one would dance after the third or fourth play, Keb Darge would often pull the record off the decks and throw it across the room.

Modern Soul (more accurately defined as 70s or 80s soul) was another big sound on the circuit. Introduced in the mid-1970s, the sound had a mixed reception. Clifton Hill (1981) all-nighter and Cleethorpes Winter Gardens embraced the sound by playing a variety of 70s soul, Jazz-Funk and Disco records. DJs such as Adam continued this culture at Stafford all-nighters and 2nd Oddfellows and introduced more contemporary records.

Every all-nighter conventionally has a final record to end the night. Dave Thorley moved away from this at Stafford to be non-conformist. Despite this, Keith Minshull was known to play Sam Bowie and The Blue Feelings- (Think of) The Times we had together.

The venue also had its fair share of live acts. In 1986 Eddie Holman performed live, footage of his performance and of the all-nighter can be seen on Chasing Rainbows EP.7 22:30-30:30

Nottingham Palais All-dayer/All-nighter (1976-1983)

The Palais started out as an All-dayer in the mid/late 70s. Later, it become an oldies all-nighter. Its main and most peculiar feature was its smaller roomed dancefloor. A circular sprung wooden board dancefloor that would slowly rotate. If you were concentrating on your footwork too much, you’d look up a few songs in to find yourself transported to the other side of the room. The venue also had a small café that served hot drinks (a common feature of all-nighters in the 80s). Bars usually closed at midnight or served no alcohol at all. Its décor was unique (to say that least) with net covering across the walls for its sea theme.

Nottingham & Leicester Oddfellows All-Nighter (1982-1987)

The Nottingham Oddfellows was promoted by Ally Mayer and Tony “the vicar” Clayton. Its name is very misleading as the all-nighter was based in Leicester, not Nottingham. This led to many punters scratching their heads when they arrived in Nottingham with no venue in sight.

The oldies at Oddfellows was more emphasized than Stafford. People have often cited the selection as the “best of Wigan”, cutting out the more dubious selections from the by-gone era. This alongside sixties newies and modern soul spins made the nighter an extremely prolific and popular. Oddfellow’s final record of the night was Donna Coleman- Take me home.

The upstairs (main) room was the sixties room that played a mix of oldies and new discoveries. Downstairs was the modern/alternative room with Adam as resident DJ. This room provided the clear crossover between Oddfellows and Stafford with a mix of modern and sixties rarities. The rooms would switch for one hour each night with the alternative/modern DJs playing in the upstairs room, and the main room DJs downstairs.

Electric theatre was the venue for the first two dos, it then moved to Oddfellows later. Central England Soul club was the name of the organisation that ran the all-nighters. Adam was invited to become resident at the age of 18 during the Electric period. Lee Vowels (RIP) also DJ’d at the first all-nighters; He was invited to do the 5th Reunion, but he sadly passed away before the event.

Oddfellows had a strong following from the Rugby crowd, Leicester natives and many others around the Midlands and the rest of the country. It often had around 300+ punters a night. At its peak, it was bringing in around 800 attendees. Even Edwin Starr turned up to one of the all-nighters.

Adam also featured as resident at Oddfellows with Modern soul sets featuring new releases. The venue would be completely dark from 11:30 till dawn due to its fake windows. This was beneficial because the morning sunlight revealing everyone at 6am is rather unfavourable! Membership was required to gain entry and you had to 18+ to gain entry. Many of the crowd from Rugby were under 18, so they often gave fake names and fake addresses.

soul boys

Despite a generally split male to female demographic on the soul scene, there has always been a malecentricism. Even through the late 1980s, the main DJs and promoters were always male. It is only in recent years that there has been an increase in female promotors (Sian-RSC, Amanda-Corfu weekender) and DJs. The only female promoter of the period was the promoter of Cleethorpes winter gardens. Female soulies were often too intimidated to enter record bars due to the snobbery displayed by male record dealers. This coincided with animosity toward the younger generation by the older crowd. Older record dealers would sometimes slam their record boxes closed onto the fingers of the younger browsers.

the threads

Fashion has never been a uniform on the soul scene. This is the product of the scene being sensationalised by the media during brief periods where it has been exposed to the mainstream. For example, the baggies and vest look was only a fashion that was worn for a short period of time at Wigan Casino. Fashion on the soul scene has always remained innovative and moved along with the times. It is the music played that remains timeless, not what people wear.

80s fashions staples such as white towelling socks, pastel jumpers, silk shorts and head bands were prevalent. You had the mod revival fashions stuff in there, to the dismay of some of the older crowd. Skinhead types suited and booted can be seen in Stafford footage.

Predominately though, most people wouldn’t fall under a certain category or label. It all appears to be a big melting pot of 80s fashion. A lot of men can be seen wearing button down shirts, suit/smart trousers and brogues. Moustaches appear to be very common as well. High end sportswear such as Lacoste had also become popular alongside other casual type brands that were popular in the era.

Girls would often wear loose black skirts etc, but shirts and trousers were also worn like the boys. Like the rave scene, the fashion was often intended to keep you cool whilst dancing. Some of the older crowd would wear jean jackets, button-down shirts and jeans. But when you watch the footage of Oddfellows, everyone maintains a sense of individuality with style.

scooter rallies

The Scooter rally scene and soul scene had many crossovers during the 1980s. Many individuals who went to all-nighters were also into scooters and went to rallies. Originally, the numbers ones of the scooter clubs would have a yearly meeting to organise rallies. Later, it was the N.S.R.A (Nation Scooter Rallys) who organised nationals.

Rallies were held all over the country, usually in seaside towns: e.g Yarmouth, Skegness, Isle of Wight, Redcar, Morecambe, Weston-Super-mare, Scarborough. There was always one Welsh rally, one Scottish rally and around 8-10 rallies a year, including one inland. Scooterists were designated a camp site to stay for the duration of the weekend.

Each town and/or city had their own individual club (e.g Mansfield Monsters). The local of my hometown is the Rugby Bear Essentials scooter club. Every club was unique, with their own design/iconography usually championed on club t-shirts.

Rally attendance sizes varied with the lowest being around 2,000 (Scottish rallies). The highest was around 12,000 at the Isle of Wight rally in 1984. But on average, most rallies had around 5,000 over the duration of the weekend.

Rallies were often a weekend long party, with scooterists invading towns and taking over boozers. Live acts were a common feature of rallies. For example, Snake Davis and the Suspicions supported many live acts, and were also good stand alone. Most rallies had all-nighters. Memberships were required to access the all-nighters hosted at rallys. These rally all-nighters often included DJs from the soul scene.

Unlike soul all-nighters, the music policy was more of a mix to please everyone. The soul played was far more commercial. Ska, 2-tone was also played throughout the night. In the mid-80s psychobilly records were also played to appease the newer demographic.

Sian says; “Personally, I got very bored with the soul they were playing at the rallies and after one year at Colwyn Bay, I must have heard skiing in the snow and 6x6 6 times a night. I stopped after this and concentrated on the soul scene.”

From mod to scooter boy

Initially, scooter rallies in the late seventies had a predominately mod revival demographic. Scooters were kept to their original design and frames, Levi 501s, Fishtail parkas, sta press, 3 button suits are all the common fashions, as seen with the image of Rugby scooterists above.

As the 1980s progressed, the emphasis upon fashion moved away and a greater emphasis was placed on the scooter. Rally goers wanted clothes that were more comfortable and practical. Combat boots, boiler suits, t-shirts, jungle greens and bomber jackets replaced previous fashions.

Rallies threw out its subscription to 'clean living under difficult circumstances' right out of the window. The loss of this self-consciousness introduced a more fun and rowdy drinking culture. Fancy dress and grass skirts became a rally trope (with people setting fire to the skirts at their mates’ expense.)

This transition wasn’t immediate, and you still had many mod types at rally’s during the 80s. The signifier of the split was when mods moved away from national rallies and started up their own. VFM rallies were ran from 1986 onwards.

Customs and cutdowns

With greater emphasis on the machines over fashion. Scooter were more heavily customised in terms of frames and engines. The introduction of the cut down in the early 1980s, marks this transition. Bootsy from Rugby was one of the first to have a street racer. His TS1 road racer was featured on the front page of Scootering Magazine.

Some took these customisations to the extreme with scooters altered to look like motorbikes (known as “choppers”). Custom paint jobs inspired by soul music, movies (e.g A Clockwork Orange) were also popular. With these custom jobs, there was a real sense of individuality and self-expression.

paddy smith patches

Every scooter rally had their own unique patch. Some of the patches were designed by Paddy Smith. Smith would only sell these patches at the rally; In recent years, these rally patches have become a rarity. Paddy would always maintain the integrity of these patches by the burning the leftovers that he did not sell over the weekend. To be in ownership of one, you had to really be there.

blowing up

By mid-80s rallies became larger and hosted several big headliners for live acts. Common acts for rallies were Edwin Starr, Desmond Dekker, King Kurt, Bad manners and Eddie Holman. Disc (Donnington) Scooter Rally 1985 (the patch seen above had Bad Manners perform as well as The Meteors).

This began to attract other crowds to the scooter scene such as Rockabillys, Psychobillys and Skinheads. Many of the newer crowd weren’t interested in scooters and treated the event more like a festival. This was where the trouble, especially with the ‘oi!’ fans who had no interest in scooters. For example, at Disc 85, someone was glassed in the throat near the front of the stage.

Disc 85 attracted around 10,000 people over the weekend. A precursor to the modern festivals we see today. There were some psychobillys and skins who did developed an interest after going to these larger more commercial rallies. However, this began to put off many of the scooterist crowd from commercial rallies such Isle of Wight.

The mid-80s period brought a lot of disorder with growing numbers at rallies. This all came to a head at the Isle of Wight in 1985. A riot perused due to the stall holders selling overpriced beer and food. The beer tent was burnt down, stall holders looted, and riot police were called in.

To make things worse, the promoters also billed Oi! bands, The Business and Condemned 84. Though these bands weren’t political, they attracted a lot of Nation Front skinheads from London. This was also applicable to Bad Manners, who also attracted bad lads. Scooter rallies did attract all sorts however, from far left and right to god squad recruiters.

Prior to this, there was always hostility from the locals, local police and local press. Headlines in the papers before rallies used to say things like: “Lock up your daughters, the scooterists are coming!” But the Isle of Wight riot made national headlines.

Trouble usually happened with the locals. The worst examples of this was Red Car where a local was killed after being hit over the head with a helmet. All the scooterists were in the nighter when the locals rolled up, pushing their faces against the glass windows and taunting them to come out. Everyone piled out and there were running battles that spread out to the front. The next day, the roads were covered in debris from pitched battles.

Great Yarmouth 1986 saw more trouble with infiltrations from the far-right onto rallies. With headliners Desmond Dekker and Bad Manners, some would say it was a ticking time bombs. Bad Manners often attracted a lot of bad lads from London. During his performance, Desmond Dekker was attacked on stage by Blood and Honour skinheads. Someone was slashed with a blade as they ran towards the stag. The security for the gig was the Mansfield Monsters scooter club (a club that was predominately comprised of scooter skinheads.) A large brawl broke out between the Mansfield Monsters and Blood and Honour skinheads.

Despite this on-going trouble throughout the weekend, the passion for scooters persisted. These instances occurred due to the high influx of attendees. For the majority, they were there to have a good time, show off their custom scooters and meet up with friends. This kept rallies and ride outs progressing into the present day. Periodicals such as Scootering Magazine are still active today.

With the beginning of the 1990s, many on both the scooter rally and all-nighter scene moved toward the rave scene. However, both scenes continued throughout the nineties into the new millennium. There were also some crossovers during this period. The legendary rave venue, The Eclipse, in Coventry had a two roomed event with a soul nighter room upstairs and the rave room downstairs.

Scooter rallies musically began to stagnate, bar adding Madchester tunes to the roster. However, some of those who organised rallies went on become organisers of the rave scene. Despite a movement away from some, rallies and ride outs continued into the new millennium.

The legendary 100 club was active throughout the 80s (but I could write a whole other article on this). By the 1990s, it had become a key all-nighter spot after the closure of Oddfellows and Stafford. Weekenders also became increasingly popular over this period. For example, Cleethorpes. Music on the scene also progressed with Modern rooms playing soulful house tunes.

I would like to thank Sian and Dean for their kind donations of photos, memberships and flyers for both scenes. I wouldn’t have been able to put this project together without them. I first met Sian and Dean at their all-nighter at the Benn Hall in Rugby. What has followed is a five-year friendship that has shaped my music, fashion and identity today.