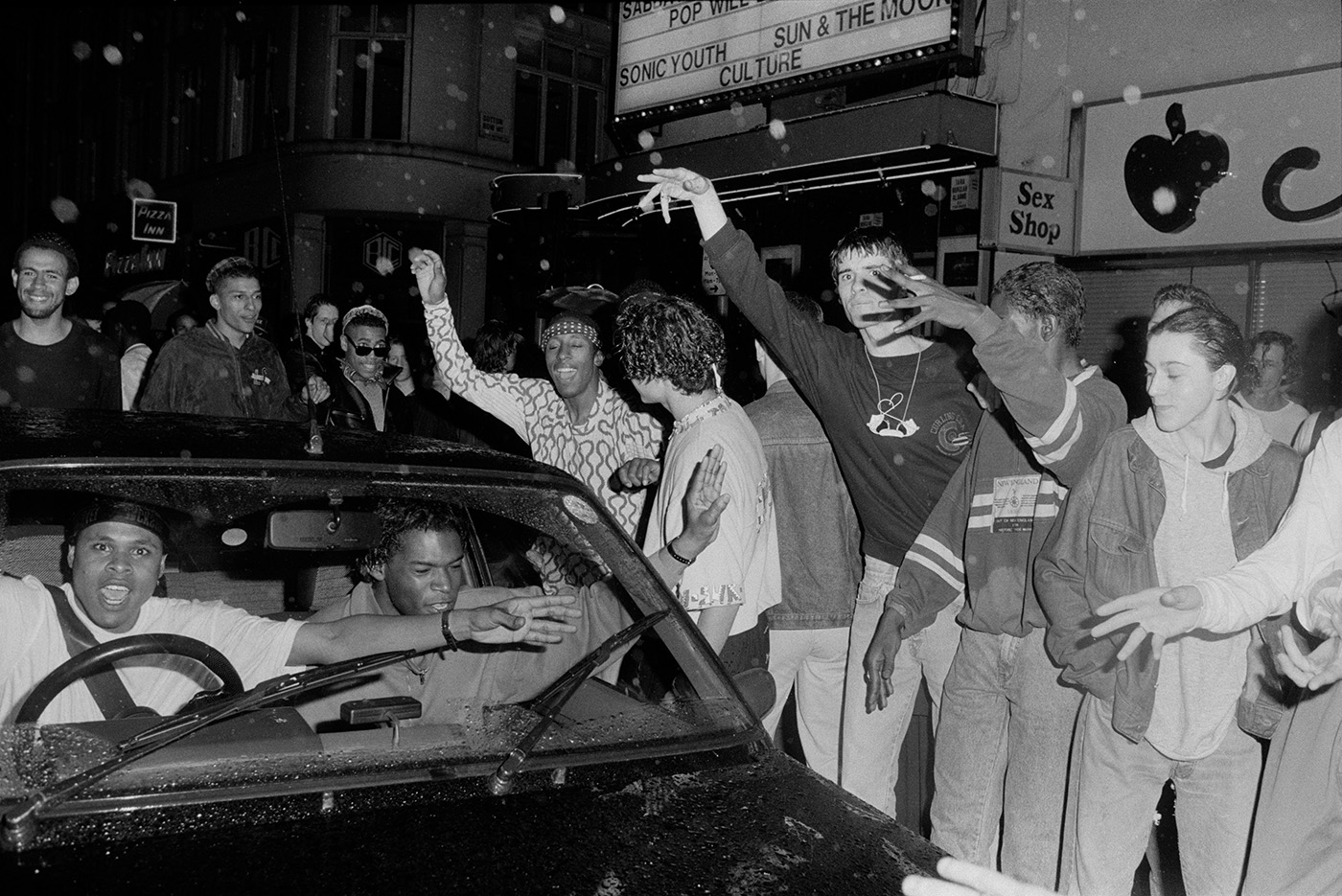

In the summer of 1988, a new kind of music appeared in clubs, abandoned warehouses and fields across the UK and it became known as Acid House. With influences from Detroit, Chicago, Germany and Ibiza, Rave was an international movement that Britain made its own. The Second Summer of Love, as the summers of '88-'89 became known, redefined nightlife for generations to come.

Text by Chris Warne, Cover Photo by Gavin Watson.

"The rave thing was really important, punks, gangs of hooligans, skinheads, rockabillies, raving wiped all that away. Raves were nuts, to have that level of freedom. I used to stand in a fucking field just feeling fucking sorry for the people that weren’t there to witness it or be part of that absolute revolution. Rave is more punk than punk ever was, because kids didn’t even think about breaking the law, they just wanted to get to a rave. The spirit was amazing." - Gavin Watson, Rave Photographer

But emphasising the newness of rave doesn’t account for how it was already familiar: in the UK it fitted easily into existing tales of subcultural independence, typified by Boys Own recycling the punk/Sideburns instruction to ‘go and form a band’, replacing guitar with decks and sampler. 1988 was the second summer of love after all. This reflects truths not fully caught by the ‘before and after’ story – there were many pathways into rave, and the journey in was not from nowhere. Acid house and rave took off because it was already recognisable, whether to veterans of the UK hip-hop and electro scenes, who knew about DJ-ing and dancing, or those familiar with the alternative nights inspired by the dancefloor eclecticism of mythical gay clubs like New York’s Paradise Garage or the Chicago Warehouse. It also made immediate sense to the free festival and party scenesters, old hands at organising unlicensed outdoor parties. It was quickly taken up by graduates of the sonic and social infrastructure of reggae and dub sound systems. In the same way, promoters and DJs from the UK soul and rare groove weekenders, accustomed to taking over holiday camps as temporary subcultural enclaves, brought their expertise to the rave scene. Even indie kids swapped their grey and black for rainbow-coloured hoodies, smiley t-shirts and dungarees. Being both instantly new and already familiar explains the unusually rapid development of rave and club cultures in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

And rapid development meant the proliferation of musical genres flowing from the initial ingress of acid house: new production technologies, especially the Akai sampler and Roland drum machine, changed the sonic possibilities for creating soundtracks for collective dancing. They meant existing musical heritages could be assembled into a new soundscape and were the cause for genre diversification: acid house’s initial unity had by the mid-1990s evolved into an apparently infinite range of genres and sub genres, differentiated by speed and sound. Balearic; Italo house; techno – split between the purist fidelity to its Detroit origins, and a drift to the Belgian-German nexus of faster beats and harder sounds; garage; progressive house; breakbeat; hardcore; happy hardcore; gabber; trance; jungle; drum and bass. This genre multiplication was paralleled by renewed energy in the rare groove and soul scenes once they were cannily rebranded by Gilles Peterson as ‘acid jazz’. And the list is incomplete without the rediscovery of ambience, cinematic soundtracks, library music and ‘lounge’ which grew out of the chill out room and after-club. Every drug experience needs its come-down soundtrack. These technologies changed how music was made, displacing the classic pop song-narrative format, moving it towards a serial sequencing of effects, where any sonic element becomes a piece in a larger jigsaw. The finished track was then itself re-sequenced by the DJ into a longer musical narrative of rise and fall, taking the dancefloor on a journey shaped by shifts in tone, mood and pace, the mixing of the familiar and the yet-to-be-discovered.

We can see the same pattern mixing of known and unknown in rave’s visual cultures. The ubiquitous flyer specialised in making the culture highly visible, but only to those who already understood the lingo, the importance of the highlighted host DJ and guest DJs, the multiplication of micro genres that would be playing, the references to ’turbo sound systems’ and ‘30K lighting rigs’. The journey to the outdoor rave itself was only for the initiated, following cryptic clues offered by pirate radio, phoneline or flyer. This local relationship between initiate and DJ was further reinforced by the latter’s instinct for playing the right song at just the right moment. Regulars could demonstrate to newcomers the right way to respond. Local scenes grew because they took over local spaces and made them their own: invading the club or warehouse, but on the wrong nights (Mondays, Thursdays), filling them with visuals, familiar faces and designated zones (second rooms, chill out rooms).

Local dance music scenes in the UK were places for encountering the new, and the already known, but all at the same time. The collective experience of sound, bodies and deliberately curated ambience created a sense of belonging where you were but knowing where you were going. While certain stories that have come out of all this have become very well-known, and acquired the status of myth, we are actually only beginning to uncover their true variety and diversity, and only just starting to understand their longer-term impact for both individuals and collectives.

Chris Warne is Senior Lecturer in French History in the History Department at University of Sussex. His research has a particular focus on the evolution of popular, material and everyday cultures since 1945.

This essay was curated by The Subcultures Network, which was formed in 2011 to facilitate research on youth cultures and social change, and commissioned as part of the National Lottery Heritage Funded project to build the online Museum of Youth Culture. Being developed by YOUTH CLUB, the Museum of Youth Culture is a new destination dedicated to celebrating 100 years of youth culture history through photographs, ephemera and stories.

The National Lottery Heritage Fund invests money to help people across the UK explore, enjoy and protect the heritage they care about - from the archaeology under our feet to the historic parks and buildings we love, from precious memories and collections to rare wildlife.

Tune In

Your Love, Frankie Knuckles, 1986

Good Life, Inner City, 1989

Sweet Harmony, Liquid, 1991

Pacific State, 808 State, 1989

Turn On

24 Hour Party People, Michael Winterbottom, 2002

Trainspotting, Danny Boyle, 1996

Human Traffic, Justin Kerrigan, 1999

Beats, Brian Welsh, 2019