From Mods vs Rockers battles on the seafront to teenagers racing down newly built motorways, the Rockers were the ultimate baddies. We will be going behind the headlines and looking at the emergence of this iconic youth culture in the 50s, from the Leather Jackets and customised bikes to the rock 'n' roll soundtrack to their life.

Text by Bill Osgerby, Cover Photo by 59 Club Archive.

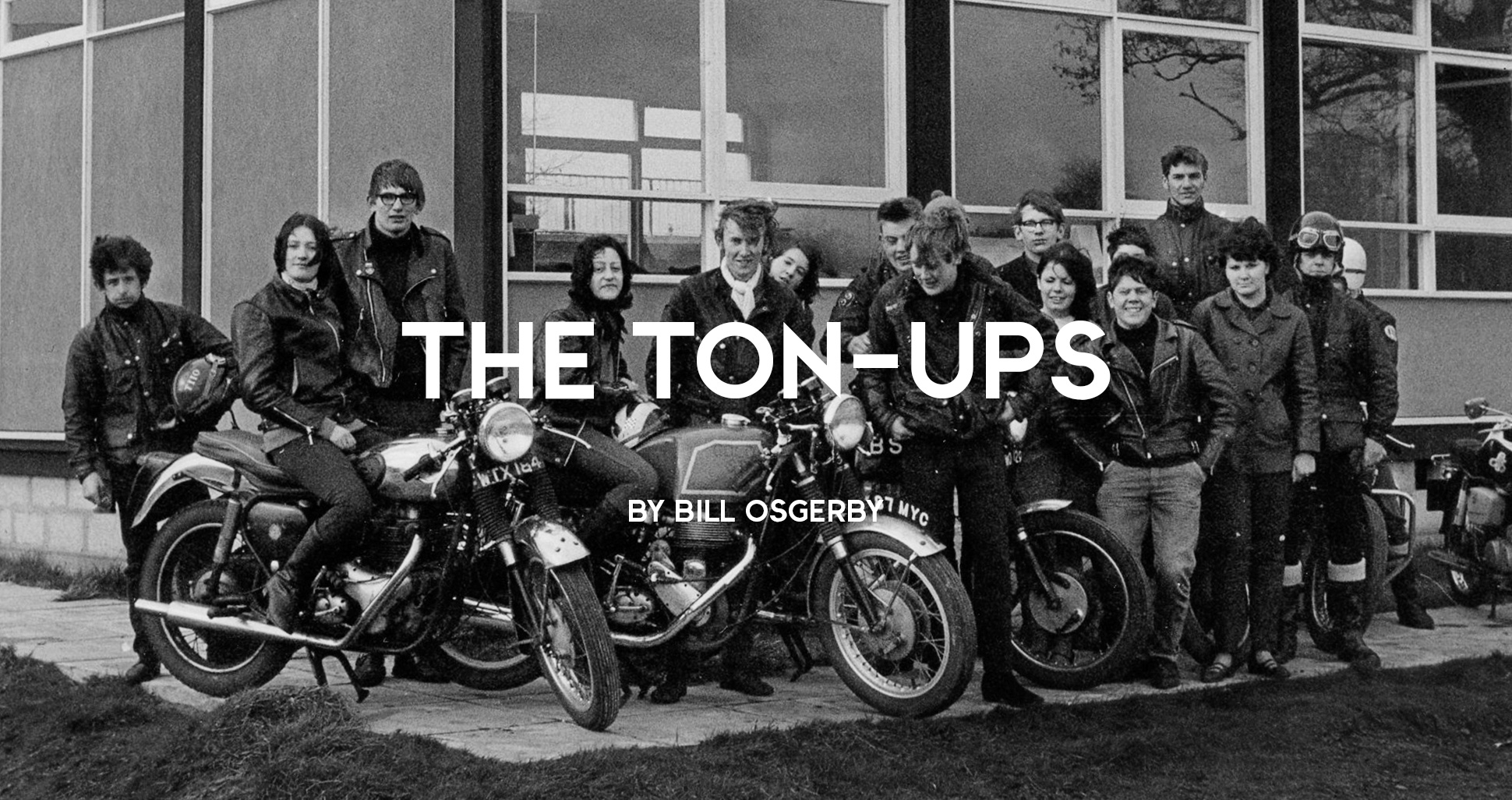

Motorcycles were big news in British youth culture during the 1950s and 1960s. The term ‘biker’ is now commonly given to young, motorcycle desperados. But, during the 1950s, they were known as ‘Leather Boys’, ‘Ton-Up Boys’ or (usually scornfully) ‘Coffee-Bar Cowboys’. And, during the early 1960s, they were commonly referred to as ‘Rockers’. For these speed-hungry daredevils, the motorcycle was more than a means of transport. It was a statement of outlook, a resolute assertion of a maverick lifestyle that offered escape from the dead-end monotony of work and home.

Postwar Britain could be a drab place, but by the mid-1950s the good times were beginning to roll. Enjoying a newfound affluence, increasing numbers of working-class kids could afford their own motorcycle – a scruffy, second-hand Triumph, Norton or BSA Twin, or even a spanking new machine bought on newly available ‘hire purchase’ credit schemes. The surge in demand marked a high-point for the British motorcycle industry, but it also pointed to the rise of one of the most distinctive youth styles of the period.

The young riders stood out from the crowd. While the Trailmaster and Barbour waxed cotton jackets traditionally favoured by British motorcyclists remained in evidence, increasingly it was the characteristic style of denim jeans and black leather jackets that proliferated. The image was partly influenced by the style of American bikers, embodied by Marlon Brando’s depiction of a motorcycle gang leader in the 1953 movie The Wild One. Screenings of The Wild One were banned in Britain until 1968 (the censorship adding to the young motorcyclist’s illicit aura), but its iconography crossed the Atlantic in movie stills and magazine features, and was eagerly adopted by Britain’s young bike crowd.

"“During its heyday in the 60s when everyone would race everywhere on big motorcycles, leaving the club on a Saturday to race to Chelsea bridge, the sense of freedom and camaraderie amongst a bunch of people with the same outlook” - Dick Bennett, 59 Club Member

Imports of US leathers were expensive and rare. But British manufacturers such as Lewis Leathers stepped in to cater for the burgeoning market of Britain’s home-grown Wild Ones. For young riders, the leather jacket could become an extension of their personality, and jackets were often decorated with an assortment of badges for clubs, racing-circuits and motorcycle manufacturers; together with a profusion of studs and the occasional painted slogan.

For the motorcycle pack, life often revolved around the coffee-bar, café or ‘caff’. Pubs of the time rarely welcomed leather-jacketed youngsters – because they tended to upset the older clientele and attracted unwanted attention from the local police. The ‘caff’, on the other hand, was warm and inviting (and also cheap), and so became the regular haunt for young British riders. It was a place where they could meet up with mates and spend smokey evenings chatting-up the ‘birds’ and spinning disks on the jukebox. And some cafés became legendary motorcycle hangouts – the Nightingale in South London, the Salt Box near Biggin Hill, the Chelsea Bridge Tea Stall, the Busy Bee on the A41 and Johnson’s on the A20.

The Ace Café on London’s North Circular Road became a particular favourite. Open 24-hours a day, the Ace could see up to a thousand bikes come in and out on a busy evening. And, after midnight − when the North Circular traffic was at low ebb − breakneck races could be held with little fear of interference. The Ace even provided the backdrop for parts of the 1964 film The Leather Boys, a ‘kitchen-sink’ melodrama (adapted from Gillian Freeman’s 1961 novel) whose location sequences captured much of the flavour of the period’s motorcycle scene.

For a while the BSA Gold Star – affectionately known as ‘the Goldie’ – was the young motorcyclist’s ride of choice. Launched in 1954, the Goldie’s ‘classic’ versions (with their distinctive, ‘big-fin’ engines) were especially admired. But riders were seldom satisfied with stock bikes. Increasingly, custom-styled and heavily modified machines became popular. Dubbed ‘café racers’, their superfluous fittings were chopped away and a racing fuel tank was bolted on, along with swept-back exhaust pipes and low, ‘clip-on’ handlebars. The ambition was for greater speed and the revered aspiration to ‘do the ton’ – a slang phrase for tipping the speedometer above 100 mph (and the derivation of the term ‘Ton-Up Boy’).

The scene saw a profusion of homemade, custom-styled machines, but a common arrangement was a powerful Triumph engine (usually a 500 or 600cc Twin) slotted into a Norton Featherbed frame. The combination offered the best of both worlds – a reliable engine that delivered an impressive turn of speed, and a lightweight frame that allowed excellent handling and road-holding. Indeed, so commonplace was the Triumph/Norton fusion that it became known as a bike in its own right – the ‘Triton’.

The ‘Ton-Up’ gang shared tastes similar to the 1950s Teddy boys. American rock ‘n’ roll, for instance, was the preferred music − Elvis, Eddie Cochran and Gene Vincent, whose image (especially their greased-back hair) was widely imitated. The jukebox, meanwhile, laid the way for the infamous sport of record-racing. The stunt involved slapping a record on the jukebox and leaping onto your bike in an attempt to complete a prearranged course before the end of the song. A popular route at the Ace Café covered a distance of 3½ miles, while massed races from the Ace to the Busy Bee, 12 miles away on the Watford bypass, were also a favourite. And, of course, Britain’s arterial road system – expanded and improved during the 1950s – provided an ideal track for many other impromptu ‘burn-ups’.

By the early 1960s the term ‘rocker’ was increasingly being applied to the young, leather-clad, rock ‘n’ rolling motorcyclists. The term was especially popularised by an overwrought media who conjured with images of fierce rivalry between two distinctive youth clans – the more established rockers and the new (and usually more numerous) mods, who were clean-cut sharp dressers with a taste for Italian scooters and American soul. Press coverage of a fracas in March 1964 at the seaside town of Clacton was especially febrile, and stoked a mod-rocker animosity that continued throughout the mid-1960s.

By the late 1960s rocker style was mutating. The term ‘greaser’ (denoting both greased-back hair and oil-stained denims) was commonly applied to a new generation of motorcycle-loving tearaways with a penchant for long hair and heavy rock music. Bikes also changed, with a growing interest in the ‘chopper’ style of high, ‘ape-hanger’ handlebars, low-slung frame and raked front forks.

Partly, the image was indebted to the appearance of American biker gangs such as the Hells Angels, whose notoriety had circulated worldwide. Inspired by the US gangs, a horde of similar groups sprang up throughout Britain during the late 1960s – Freewheeling Wessex, the South London Nomads, the Glasgow Blues and many others. A number of unofficial ‘Hells Angels’ groups also appeared, but it was only in 1969 that official Hells Angels charters were granted to two London Chapters, followed by a West Coast Chapter in 1974. And, since then, the image of the badass biker has retained a prominent place in Britain’s line-up of subcultural anti-heroes.

Bill Osgerby is an author and professor with a focus on modern American and British media and cultural history — with particular regard to the areas of gender, sexuality, youth culture, consumption, print media, popular television, film and music. Amongst other he has published, Youth in Britain Since 1945 and Biker: Style and Subculture on Hell’s Highway

This essay was curated by The Subcultures Network, which was formed in 2011 to facilitate research on youth cultures and social change, and commissioned as part of the National Lottery Heritage Funded project to build the online Museum of Youth Culture. Being developed by YOUTH CLUB, the Museum of Youth Culture is a new destination dedicated to celebrating 100 years of youth culture history through photographs, ephemera and stories.

The National Lottery Heritage Fund invests money to help people across the UK explore, enjoy and protect the heritage they care about - from the archaeology under our feet to the historic parks and buildings we love, from precious memories and collections to rare wildlife.

Tune In

Summertime Blues, Eddie Cochran, 1958

Jailhouse Rock, Elvis Presley, 1957

Be-Bop-A-Lula, Gene Vincent, 1957

Rock Around The Clock, Bill Haley & His Comets, 1955

Turn On

The Wild One, Laslo Benedek, 1954

The Leather Boys, Sidney J Furie, 1963