British Asian Dance Culture

As dance music swept across the UK in the late 80s and early 90s, it provided a safe space for new genres and music to emerge. Within these exciting times, the British Asian community carved out a space for the Asian Underground Movement, fusing the new sound of electronic music with their Asian roots.

By Neil Kulkarni | Cover Photo by Adam Friedman

Music, dance and culture have a special place in the life of migrants both as a way of staying in touch with your roots but also creating a space in which new realities and struggles can be absorbed and reflected. From its ancient roots in the subcontinent Asian music has accompanied successive waves of Asian migrants to the UK and while the subcontinent – and particularly its vibrant ‘Bollywood’ film culture – has remained the musical source for much British Asian music, a distinctively British variant of Asian music has emerged ever since the first waves of migration of Asians from India, Pakistan and Africa in the 60s and 70s. Mutating and forming hybrids with Western pop forms British Asian dance culture has reflected the increasing confidence of British Asians and challenged the dominance of Western pop on the British cultural imagination.

For a long time, British Asian Dance culture was strictly an underground, almost familial phenomenon, confined to the wedding circuit and private parties of Britain’s Punjabi community. In the 70s and 80s, in suburban and inner-city areas of London and Birmingham, pioneering groups such as Alaap, Heera, Golden Star, DCS and producers such as Kuljit Bhamra reworked traditional Punjabi folk music with new electronic production technologies and techniques. This new metropolitan form of ancient rural music, called Bhangra, was a result of processing traditional dhol and drum beats and Punjabi folk melodies with synthesisers and samplers, with a heavier bass line and mixed with western pop and black pop rhythms. Cheap mixtapes, and the rise of Asian DJs, soundsystems and a remix-culture fostered the genre’s popularity, especially with British Asian kids. Crucially, where India found itself increasingly fragmented by political and religious strife, Bhangra became a way for British Asian youth to unify against the racism they encountered from mainstream British culture, the music acting as a point of solidarity and identification for kids whose parents were from across subcontinental religious, national and regional divides. In the 1980s, distributed by record labels such as Multitone Records, Bhangra artists were selling over 30,000 cassettes a week in the UK but because these tapes were sold in Asian stores unrecorded by the official UK Charts company it never cracked the UK charts to ‘cross over’. Stars like Channi Singh, Malkit Singh, and bands like Apna Sangeet, Heera and Alaap remained entirely unknown outside of the Asian community. Bhangra remained, and remains, an underground phenomenon- its idiosyncratic and culturally specific Punjabi lyrics, and camp macho imagery made it a significant subculture within the Asian community in the 80s and perhaps the true ‘real Asian Underground’. By the late 80s however, things were changing.

"Music, dance and culture have a special place in the life of migrants both as a way of staying in touch with your roots but also creating a space in which new realities and struggles can be absorbed and reflected."..."Mutating and forming hybrids with Western pop forms British Asian dance culture has reflected the increasing confidence of British Asians and challenged the dominance of Western pop on the British cultural imagination."

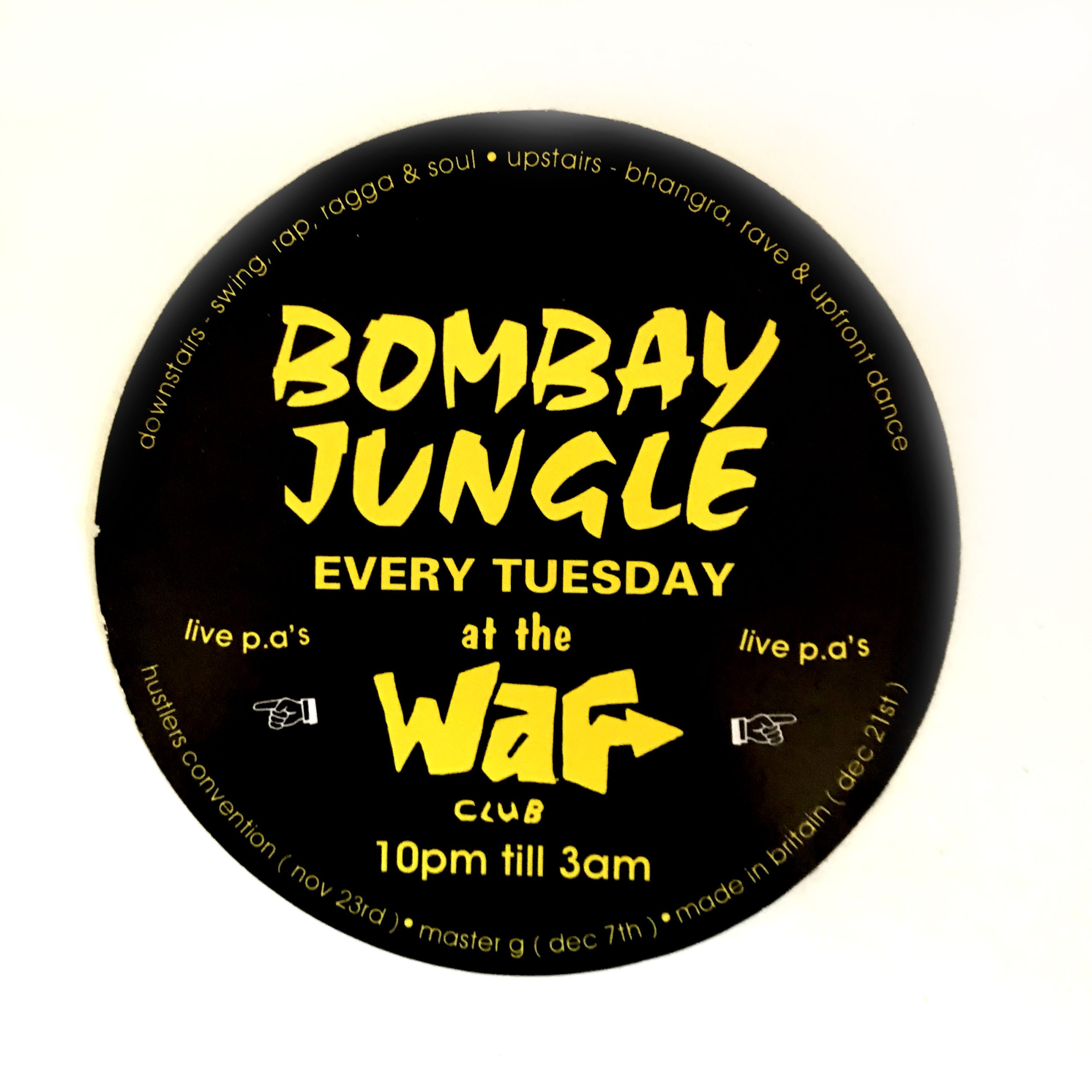

Changes in music technology and the rise of DJs like Bally Sagoo and Panjabi MC shifted and altered the sound of Asian dance culture. Initially hired by Bhangra labels like OSA and Nachural to remix original bhangra recordings these DJs quickly found that remixing original folk singers from India was much cheaper than working with outsourced Bhangra bands. Hip hop culture started percolating through to this new Asian underground, tumbi & dhol samples replacing band line-ups, and totally new bands like Fundamental, Asian Dub Foundation and Hustlers HC created new forms of militant, politically charged Asian rock, hip hop and dance, infused with Indian folk-samples and with a new harder-edged sound. This array of diverse artists, reductively christened the ‘New Asian Kool’ by the music press, wanted to break out of the isolated, almost hidden confines of the Bhangra scene, and bring their music, and their rage at UK racism, to the fore. Along with DJs and producers like Nitin Sawhey, Bobby Friction and Talvin Singh this new generation of UK Asian musicians took Asian dance music out of the private parties and weddings that had previously been its refuge, and took the music to clubland, making it an integral part of the mainstream metropolitan music scene. Club nights like Outcaste and Anokha in London bought together bhangra, Asian beats (or ‘desi-beats’ as its creators dubbed it), hip hop and dance music for a young racially mixed audience. As a DJ/Producer-centred culture Asian dance music found itself increasingly juxtaposed with a multitude of different Asian sounds and sources – from the classical explorations of Bismillah Kahn to the Quawaali vocals of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan – Asian youth, empowerd by new sampling technology, found new ways of recycling their roots to map a new future. The Asian underground was becoming the Asian Overground, a vibrant club scene based around nights like Raha, Shakti and Club Kali that have massively increased the diversity of city club-life. Traditionally marginalised female performers like Radical Sista, DJ Ritu, Amar & Hard Kaur have also been bought to the fore. No longer hidden, no longer isolated, British Asian Dance culture is out and proud and still changing. A soundtrack to the growing confidence of its fans and its creators.

Neil Kulkarni has been writing about hip hop music for a quarter of a century and is the author of 'The Periodic Table Of Hip Hop', 'Eastern Spring' and 'Bring The Noise: The Stories Behind Hip Hop's Biggest Songs’, as well as being the Hip Hop editor at DJ Magazine.

This essay was curated by The Subcultures Network, which was formed in 2011 to facilitate research on youth cultures and social change, and commissioned as part of the National Lottery Heritage Funded project to build the online Museum of Youth Culture. Being developed by YOUTH CLUB, the Museum of Youth Culture is a new destination dedicated to celebrating 100 years of youth culture history through photographs, ephemera and stories.

The National Lottery Heritage Fund invests money to help people across the UK explore, enjoy and protect the heritage they care about - from the archaeology under our feet to the historic parks and buildings we love, from precious memories and collections to rare wildlife.