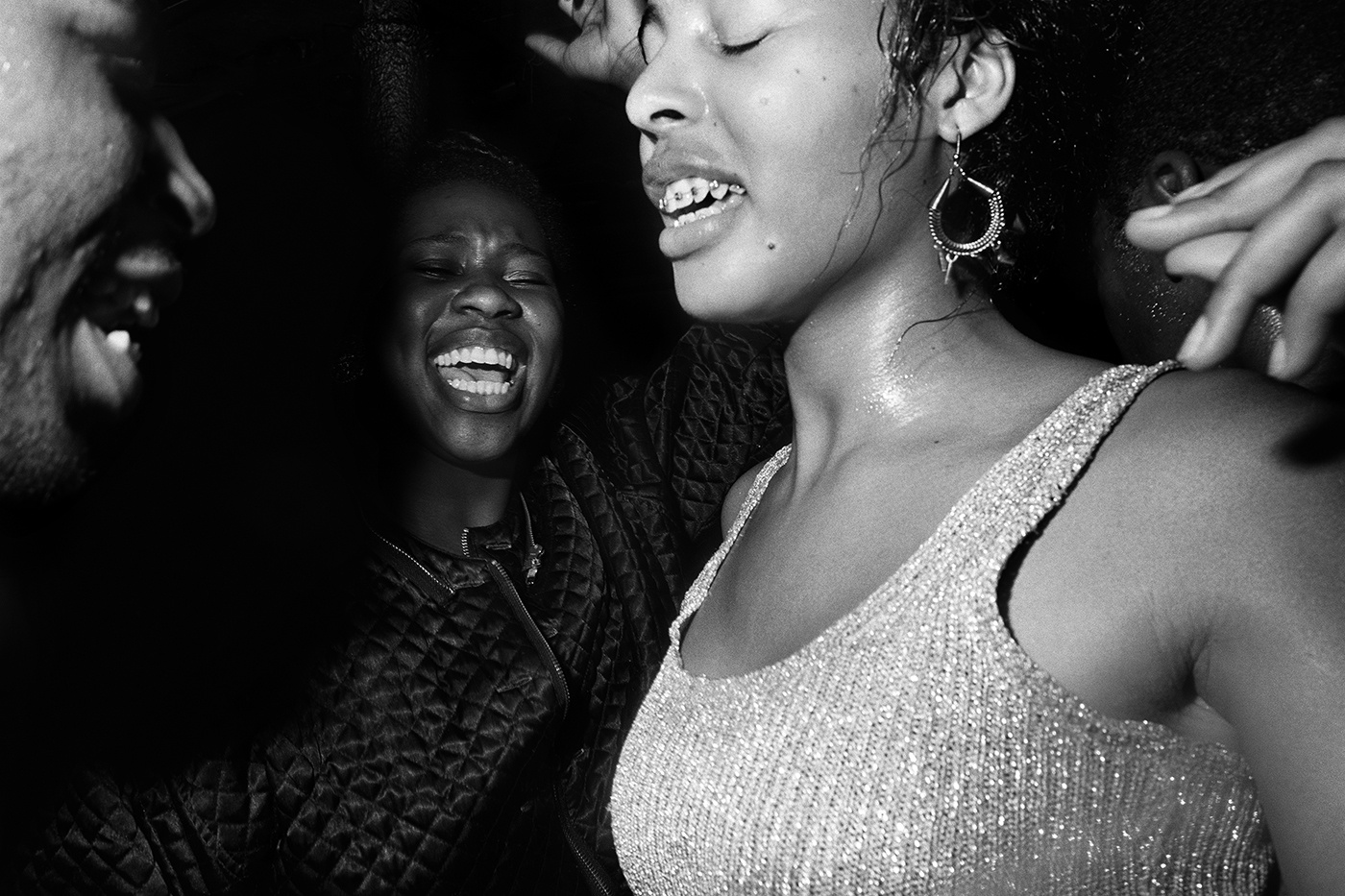

Going on your first night out to a club has become a coming-of-age passage for many young people across the world and nightlife venues are dotted in towns and cities internationally. This exhibit will give a brief history of the emergence of club culture, from the ballrooms of the 1800s to today’s illegal raves.

Text by Catharine Rossi, Cover Photo by Peter Anderson.

The origins of club culture are as murky as the memories of a night out itself, whether spent in a sweaty nightclub, an abandoned warehouse or at an open air raves. Its ancestors lie in the ballrooms and dancehalls of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which blossomed into the jazz clubs, record hops, disc sessions and discothèques in the 1940s and 1950s youth culture explosion. By the 1970s discos had spread across many parts of the world, and DJs provided the soundtracks for dance floors in cities from New York to London, Johannesburg to Hong Kong. Contemporary club culture though is really a product of the 1980s and 1990s, when clubbing became a mainstay of youth culture and broke into mainstream consciousness, assuming both transgressive and corporate traits.

Different cities have been instrumental for club culture at different times, often in dialogue with other places, people and genres. Influenced by European acts such as Kraftwerk and New Order, as well as electro and funk, in the 1980s Chicago and Detroit pioneered House and Techno. These sounds then came to Europe, becoming a mainstay of German club culture: the 1991 opening of Tresor started Berlins’ transformation into a clubbing capital, a status cemented by Berghain’s opening in 2004. With a look and sound influenced by New York clubs such as Danceteria, Manchester’s Haçienda, established in 1982, became a cathedral for Britain’s exploding club culture later that decade. A 1987 visit to Ibiza proved transformative for British DJs such as Danny Rampling, who channelled the Chicago-influenced, Balearic island’s acid house sound through London’s Shoom club, co-founded in 1987 with his then wife Jenni, one of many overlooked women in club culture’s history.

"The origins of club culture are as murky as the memories of a night out itself, whether spent in a sweaty nightclub, an abandoned warehouse or at an open air raves."