Russell Boyce

new town youth

Always interested in people and what they get up to, photographer Russell Boyce quickly became a part of the local community in Peterborough after moving there aged 23. For over a year he documented the many youth organisations in the small but diverse town, creating a project that documents everyday life in 1980s England.

Speaking to the Museum, Russell discussed the legacy of the project and how he immersed himself into the community. "I sort of became like a fixture or part of the furniture and then eventually, they all just ignored me and then I was able to float in and out and take pictures".

Interview and text by Esta Maffrett | 13.10.21

How did you get into photography and come about getting commissioned to document youth groups in Peterborough?

I went to art school as a painter, that's what I was interested in doing, I was always interested in painting people and activities. I was painting and drawing outside Bob Carver's fish and chip shop and one of my tutors, Daniel Meadows, suggested that I took a camera down there. I took the camera down and started taking pictures and I was immediately gripped. You can produce an image in 1/25 of a second which really suits my personality. So from there, I actually began to photograph people and it was like a camera is almost like a passport into, into people's lives. When I left college I moved to Peterborough and had no income. What I was fascinated by was basically the diversity of the people in the town, even though it's an old sort of industrial town. I was very interested in the struggles that were happening. I was a young person as well, I was 23, and there was a lot of unemployment at the time, I think it's 1 in 5 unemployed. I just wanted to start taking pictures. There's a road called Lincoln Road where there was quite a diverse community and I came across the Cambridge Community Centre, which is where the Friday Club is, and went in to talk to the guy, Brian Healy, who ran it and said, ‘Could I come along and take some pictures?’ Just like that in those days, you could walk in and ask to take pictures. He said yeah and asked me what I wanted to do and I said ‘Well, I'm just interested in people and what they're doing’ and he said come along. I was earning a little bit of money teaching evening photographic courses at the Arts Centre helping adults process film and make prints. At the same time, I was working part-time, in a clothes shop to get a bit of money. I started taking more pictures, Brian was well connected with that community and then he began to introduce me to people and then I would talk to more people. As well as this I was going to the Asian Cultural Centre and I asked Ansar Ali (The ACC Coordinator) ‘why aren't there many girls here?’ He explained to me about the tensions towards the community, they felt there was a lot of racism towards them. And also within the community there were tensions where women and girls wanted more freedom to do other things. And so he introduced me to Mrs. Hussein who ran the Goulistan Girls Group. That’s how it all mushroomed. Start with one thing, you meet other people, and then it grows and grows. I got a small grant, tiny, from Peterborough Arts Council. They gave me 100 quid as a fee and 50 quid for materials and that was really to document the Friday Club and the City Centre. Then I just carried on working and because I had little bits of work here and there I was able to fund it myself. It took a whole year.

Because I was hanging around, the people that were joining the clubs would ask what I was doing and I would give them my cameras, they would go take some pictures and of course, every time I did that they would shoot a whole roll of film and it cost me two or three quid which I didn't have. Sometimes the pictures were okay, sometimes terrible, you know, whatever. But it was a way to communicate and they began to think I was okay. I was a little bit older than some of them but not much, when I could I'd give them prints. I sort of became like a fixture or part of the furniture and then eventually, they all just ignored me and then I was able to float in and out, take pictures and that's when you really begin to get those special pictures.

Can you explain further the research and the decisions behind getting in contact with the groups you chose to photograph?

With the Goulistan Girls Group, Mrs. Hussein was keen that I did it but she was facing lots of pressures from within her own community because she was trying to encourage girls to develop beyond what was expected of them. And at the same time, she was having to balance the fact that the community would try and close it down if they thought that she was overstepping the mark. So by allowing me to take pictures she was really pushing the boundaries there. I went two or three times and I think it was creating problems for her so I stepped away. As I began to take more pictures and photograph more groups, people got to hear about me. That's why I was able to take pictures down at the unemployment centre, Amanda Hemmingsly (Centre Director) invited me to come in. From spending time there, I then got invited to go to Ananta’s which was the home for the homeless young. It all took time, and the people have to trust you and realise you weren't there to exploit them. I was just there to document their daily lives in a way that was fair, that was important to me.

I'm very good at waiting. The communications people have now are instantaneous but back then if you missed somebody you couldn't just call them on the phone or text them you'd have to go to where they worked or where they lived and leave a note. No one could afford coffees really so you would meet at a certain place, I'll see you on the corner of so and so Street and then that might happen, it might not. You had to invest a lot of time. But it was always worth it. Because then when you did get access, then suddenly it would be fantastic access and they would completely chill out and let you take pictures.

"I think what I'm very interested in is a slice of time which is then archived for the future. So whether you learn something from it or not is really up to you but it's actually about recording something. I'm very interested in the ordinary"

New Town Youth

It is 1985, ‘International Youth Year'. Margaret Thatcher has been Prime Minister for six years and Britain is struggling out of a deep recession, unemployment stands at 11%, inflation 6% and interest rates 11.4%. Youth unemployment is one in five for those under 18 and even higher for those age 16 to 17, at 23%*. Many leave school at 16 to start work, but end up signing on the ‘dole’ for benefits, or join the controversial Youth Training Scheme (YTS). Under 15% of 18-year-olds go to university.

Peterborough is a ‘New Town’, conceived to provide large areas of new housing and job opportunity and in 1985 was rapidly expanding. It was a community trying to shape itself. For the year of 1985, Russell Boyce, then aged 23, was commissioned by the Peterborough Arts Council to document youth groups in Peterborough. These diverse settings included youth clubs, school dance groups, a YTS worker, a youth unemployment centre, a home for the homeless young, the Peterborough Youth Trust which was a scheme to help young offenders, the Asian Cultural Centre, The Goulistan Girls Group and cultural exchange gatherings. Here are his picture stories.

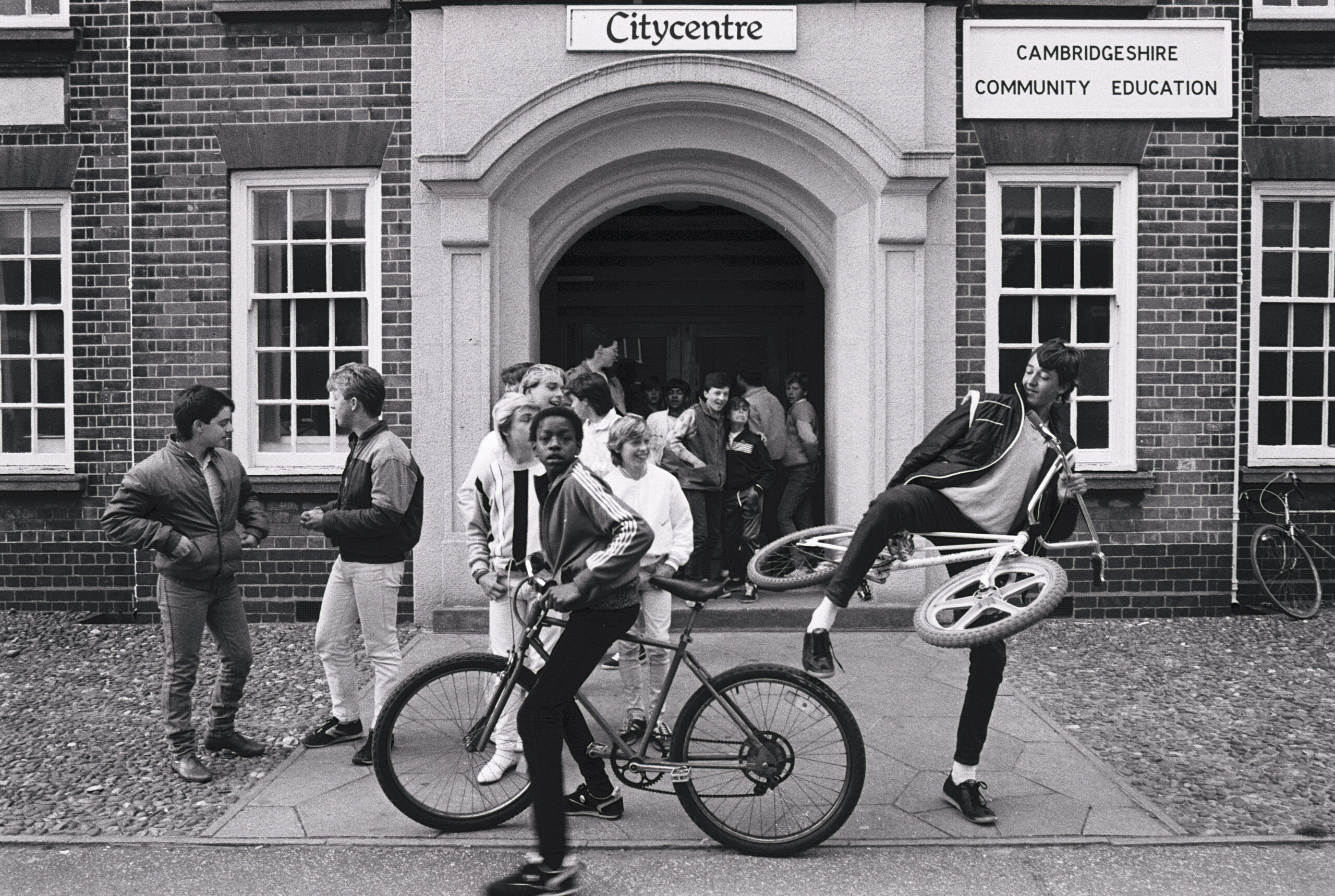

The Friday Club was a youth club that operated under the umbrella of Cambridgeshire Community Education at the City Centre building in Lincoln Road, Peterborough. City Centre was funded by the Cambridgeshire County Council and by money raised by individual clubs. Money was always tight. The building was seen as a community resource and was not only used by the youth club but also by many other groups.

Friday Club had a discussion group which examined subjects like racism, drug abuse and contraception. City Centre provided a 24-hour telephone service where young people could talk anonymously about anxieties they may have had. Worries could be discussed in total confidence, an important outlet for many adolescents.

The manager Brian Healey wanted the centre to be a place where young people of all ages, gender and race could learn to express themselves to their peers and adults. He said in 1985, ‘If a person is able to feel a sense of achievement through self-education and expression, then City Centre is working.’ He also added, ‘City Centre should be measured by the achievements of individuals and not by the number of people who attend the groups’.

The Asian Cultural Centre was sited close to the City Centre Education building on Lincoln Road, and many members attended both clubs. The Asian Cultural Centre was co-ordinated by Ansar Ali and was set up to both provide a place where young Asian people could socialise, and to meet the needs of the large and growing Asian community in Peterborough. ‘The Asian community has the right to carry out their traditions within Peterborough’, he said in 1985. ‘It is up to the people of Peterborough to find pleasure and not resentment in these activities. The centre has two priorities, to provide a base for activities for the Asian community and to offer a rich source of culture to those who are not Asian. We have events including cultural exchanges, lectures by political and religious leaders and dance’. Many of the groups were heavily male dominated and Ali said at the time, that ‘this is a factor that is determined by religion and tradition, something which should be respected’. At the time the pictures were taken Ali’s position was under threat due to funding cuts.

In the Asian Peterborough community, once Muslim girls reached a certain age they were no longer allowed to mix with boys. Mrs Hussain set up the Goulistan Girls Group as she said, in 1985, ‘Girls and women often take a second place to men and boys within their own community and also face racism and isolation within the wider community.’

At the group girls learned to read and write Urdu, explore religious scriptures and learned practical skills like needlework and housekeeping; everything was fun-based and games of tag and cricket were common, but all boys were kept well away to maintain a sense of tranquillity. Under the guidance of Mrs Hussain, the group went from strength to strength. It began in the back room of a house, then moved to mobile classrooms at a school and had recently been allocated a much larger building. Funding was slowly being found to help grow the group and more girls were joining.

Despite her success Mrs Hussain said at the time, she felt she had to continually deal with two major problems; racism from the resident community in Peterborough and suspicion from the Asian community who were worried that the girls would not be brought up in the proper fashion. Some Muslim parents were concerned that traditional customs would be destroyed and religious boundaries transgressed. To counter these concerns Mrs Hussain stressed the Goulistan Girls’ Group was not a social club but an event where girls and young women could meet to learn. In addition, cultural exchange meetings were set up with locals in homes to share ideas on food, dance, fashion and culture. Mrs Hussain was finding more parents began to trust her but still felt there was quite a way to go yet.

Young People’s Theatre Company (YPTC)Young People’s Theatre Company was based at Bretton-Woods Community School, funded by the Peterborough Arts Council and run by Yvonne McGuiness. It was open to 14 to 21-year-olds and evolved and grew over the previous five years by word of mouth and reputation. In 1985 Yvonne said its intention was for the group, ‘to give effective expressive voice and status to the thoughts, feeling, experiences and culture of young people’. Yvonne added, ‘The group attracts many young people who are considered the so-called alienated and disaffected youth throughout Peterborough’. Yvonne continues ‘We actively encourage a multi-ethic membership, many of the members are unemployed. Because of the collective and co-operative method of organisation, responsibilities are shared and commitment is high.’

Yvonne also said ‘Members rehearse in the evenings, weekends and during school holidays. They work very hard and usually have a great time as they are doing something that they believe in. They have control over their material, the style and its performance. The shows are always improvised using the language of young people, dance, music and theatre. The process of talking and devising is creative and educational. The members grow throughout the process. They learn about themselves, about working with a group and about ideas and issues. Many of the kids have experienced oppression in different ways but racial tension doesn’t exist, they are united.’

There were many activities available for people at the different community centres on Lincoln Road, near the Cambridgeshire Community Education City Centre building, that went beyond their core programs. Often young people would join different groups taking part in what was on offer in different centres. Some groups were created to support the needs of the community, others to offer an opportunity to try something new and some to create a space where people could meet. Although funded by the council, money was always in short supply, so groups would hold fund raising events; a hall that was used for gymnastics one night would be turned into a flea market venue on another. What was never in short supply was the willingness of people to help.

There are many small bands that spring up and fade away as people go through their teens and early 20’s. Peterborough in 1985 was no different with bands such as The Uprising, The Detours, The Frantix and The Jilted Brides all practising in the Guildhall, which was built in 1671 to commemorate the restoration of the monarchy. I liked this irony as the bands belted out their anti-establishment songs. I asked each band how they’d like to be photographed. Some wanted formal studio portraits, the Detours wanted to look mean and lean in the streets of Peterborough while others were just happy to be photographed where they stood in the Guildhall. They also provided the lyrics of the songs they had written, with some common themes then as now.

In 1985 under Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government, Britain had come out of a deep recession but unemployment rates were still very high, countrywide about 11%*, over three million people. Youth unemployment was even higher, one in five for those under 18 (16 to 17-year-olds, it’s 23%). These figures did not include people who were on Employment Training Schemes, which included the Youth Training Scheme (YTS). The YTS was described as on-the-job training for school leavers (aged 16- 17) but critics claimed it permitted employers to exploit school leavers for cheap labour and disguise true youth unemployment rates.

In 1985, YTS worker Amanda Fields was paid £27.30 for a 37.5-hour long week working in Collier menswear shop in Queensgate shopping centre. She said at the time, ‘Beggars can’t be choosers.’

* Figures from the Office of National Statistics

‘No experience – no job. No job – no experience,’ was the vicious cycle of youth unemployment that Director Amanda Hemmingsly was trying to break with the council funded Westgate project in 1985. The centre provided a phone, a typewriter, access to employment information, information about social security rights, a pool table, table tennis and badminton. According to Amanda, what it most importantly provided was communication with other people who faced the same problem and a day- centre for many of the young people who were sleeping at Ananta’s.

Ananta’s, in Cromwell Road, Peterborough was the place where homeless young could sleep and was considered the last safety net before they were forced to sleep rough on the streets. Ananta’s was closed during the day so the residents spent the day in the streets or at the Westgate Project, trying to seek help, warmth and company. These young people had no work and lived a hand-to-mouth existence with social services. The housing waiting list was long, but slowly a lucky few were housed in bedsits – others continued to dream and wait for a place of their own to sleep. Once in the cycle of homelessness and unemployment it was hard to break. Employers were fearful that young people would fail to turn up for work as their lives were so erratic.

This is the story of three people, I called them Paula, Julie and Sean (not their real names) who in 1985 wanted their story documented. Their lives were intertwined and representative of many in their situation, trapped in the cycle of youth homelessness and unemployment. In Britain, in 1985 unemployment was 11% but youth unemployment was even higher, one in five for those under 18. For those age 16-17, it was even higher at 23%. At age 18-24 the jobless had shrunk slightly to 19%.*

*Figures from the Office of National Statistics

The Peterborough Youth Trust was a pilot scheme set up in 1985, which offered Juvenile and Crown Courts an alternative to custodial sentences for young offenders, or children whose parents could no longer control their delinquent behaviour. The age range was between 10-17 and many had come from a background of broken homes, poverty and poor housing; many had been in care. The aim was to integrate the offender at youth, hobby and sports clubs to help them break away from their delinquent sub-culture. The hope was to develop a new pattern of non-offending, a daily routine and final integration back to school, with the help of specialist teachers. Many school age offenders were serious truants.

‘These teenagers do not need a brutal short sharp shock or detention,’ said one of the outreach workers, in 1985. ‘They need to be reintegrated slowly to a non-offending environment through our work. That takes time and patience. Custody only further isolates people who already feel isolated.’ Does PYT do any good? ‘Yes, but the effect is not always immediately obvious.’

My time spent with ‘Mark’ (not his real name) was a two-way street. As part of the pilot scheme, I was asked to help show him how to use a camera to shoot pictures, process film and make prints, while being able to take a few images myself as he learned. I shot very few images as I wanted to help him learn a new skill, and it was agreed not to show his face, so some images are pixelated.