Most places you go you will find skaters cruising the street and landing tricks in skateparks. When thinking in historical terms, we often look to USA for its emergence, but the scene has been just as big in the UK. Explore the history of Skateboarding in the UK and how it hit the mainstream.

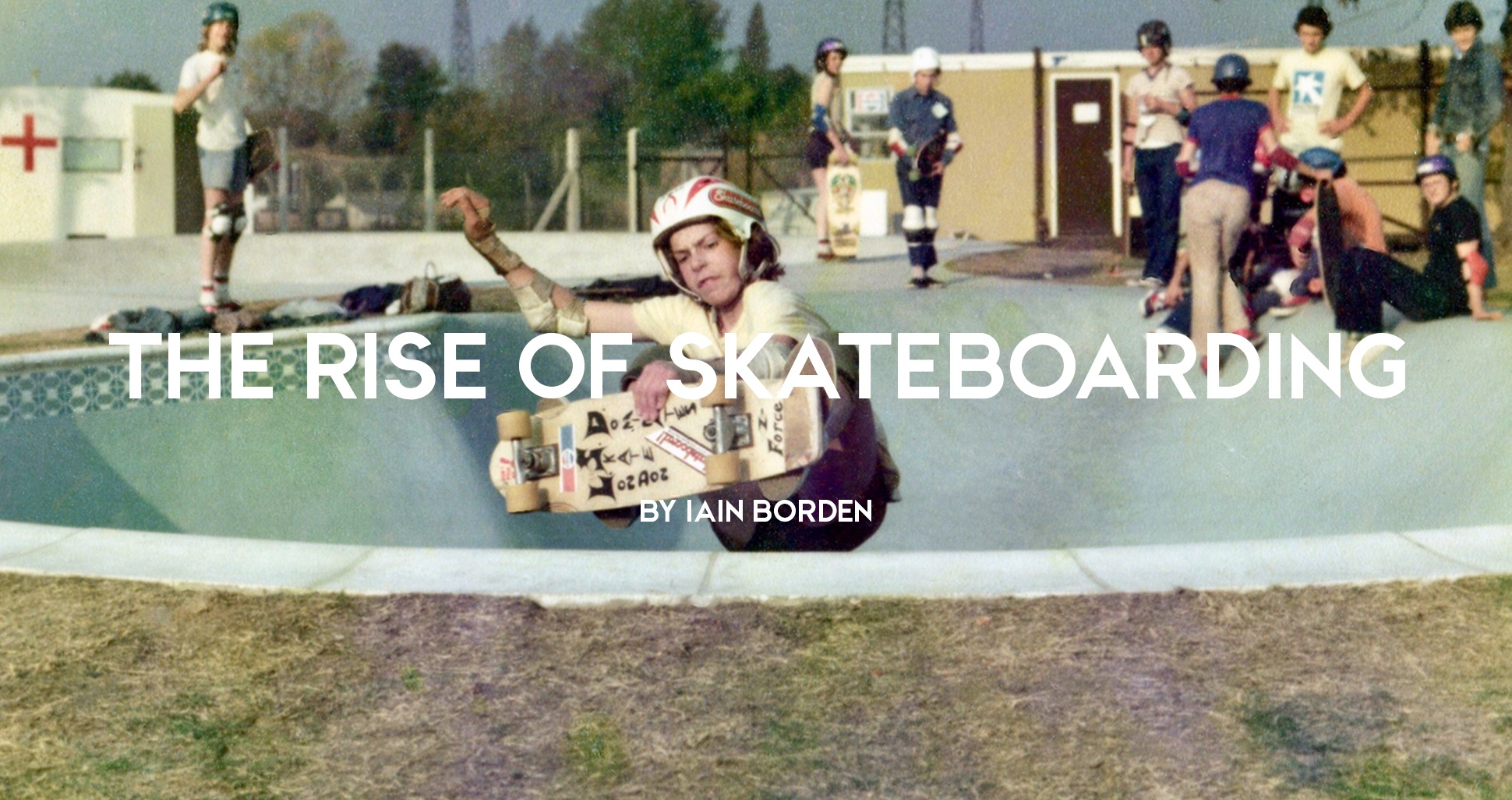

Text by Iain Borden, Cover Photo Public Submission by Zoe Gaiger.

Skateboarding first began in the USA during the late 1950s, when frustrated surfers rode basic skateboards fabricated from hard wheels, roller-skate trucks, and narrow wooden decks. In the UK, British Pathé News excitedly reported on this new phenomenon, which was enthusiastically adopted in surf-focused St. Ives in Cornwall and Langland Bay in South Wales, and by cosmopolitan London riders.

Skateboarding’s next big wave came in the mid-1970s with the adoption of polyurethane wheels, more sophisticated truck designs and wider decks. From 1976, a slew of commercial concrete skateparks opened across the USA, beginning with Florida’s SkatBoard City and California’s Carlsbad. In these skateparks, the wave-like walls of snake runs were inspired by surfing, while bowls, pools and half-pipes were based on suburban swimming pools and American drainage infrastructure.

UK skateboarding now took off, fuelled by Skateboard! magazine and the BBC “Skateboard Kings” documentary. Commercial skateparks also appeared, including Earth’n’Ocean (Barnstaple), Watergate (Cornwall), Rom (Essex), Kelvingrove Wheelies (Kelvingrove), Skate City, Harrow, Rolling Thunder and Mad Dog Bowl (London), Malibu Dog Bowl (Nottingham) and Skateopia (Wolverhampton).

Issues with insurance and commercial viability, however, meant that most quickly closed, and skateboarding fell into a slump, kept alive by a few die-hards riding on the few surviving skateparks and above-ground 10-ft-high high wooden ramps called “half-pipes. Notable examples were constructed at Hastings, Swansea, Farnborough, Warrington’s Empire State Building and London’s Latimer Road and Crystal Palace. R.A.D. was the pre-eminent magazine, while Skateboard! also kept the scene alive.

Into the late 1980s and early 1990s, and skateboarding underwent a massive shift, with the arrival of innumerable small skater-owned companies and more accessible street-based riding. In contrast to the advanced gymnastics of half-pipe specialists, the new breed of street skaters deployed the “ollie” move (kicking down on the board tail, making it jump back into the air) to turn ordinary pavements, ledges, benches, handrails, steps and planters into a new playground of pleasure.

Released into the streets of towns and villages across the country (places like Milton Keynes, Oxted, Ipswich, High Wycombe and Cirencester became as famous for street-skateboarding as Bristol, Edinburgh, Cardiff and London), while being documented by Sidewalk magazine and captured by cheap camcorders, skateboarding rapidly developed into a full-blown Generation X subculture, with its misfit participants, distinctive clothes, obscure language and alternative occupation of city spaces all casting it as a rebellious even counter-cultural entity.

Simultaneously, skateboarding was mutating once again. By the end of the 1990s, the spectacular cable TV-oriented X Games and the incredibly popular Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater video game, plus a growing realisation that skateboarding could offer powerful entrepreneurial, artistic, socio-cultural and health benefits, all transformed the attitudes of skateboarders and non-skateboarders alike. In particular, new Generation Y skaters no longer demonstrated the overtly anti-commercial suspicions of their predecessors, actively embracing brands as part of skateboarding’s nascent mainstream identity.

"It seems as though skateboarding is finally being seen in its true light: at once critical and caring, rebellious and entrepreneurial, non-conformist and mainstream, and so as a dynamic presence in cities worldwide."

All of this can be seen in the world of UK skateboarding today. At places like the Undercroft in London and Rom skatepark in Essex, skateboarding has lead debates over matters of public space and architectural heritage, and has secured widespread public and institutional support. Hundreds of new skateparks have been constructed across the UK, some of which, like F51 (Folkestone), Factory (Dundee), Transition Extreme (Aberdeen) and Adrenaline Alley (Corby), offer extensive community outreach programmes. Social enterprise organisations like The Far Academy, SkatePal, Free Movement and Skate Nottingham similarly engage with hard-to-reach youth, refugees and other disadvantaged members of society. Skateboarding here acts as a force for the good, positively contributing to community and urban life.

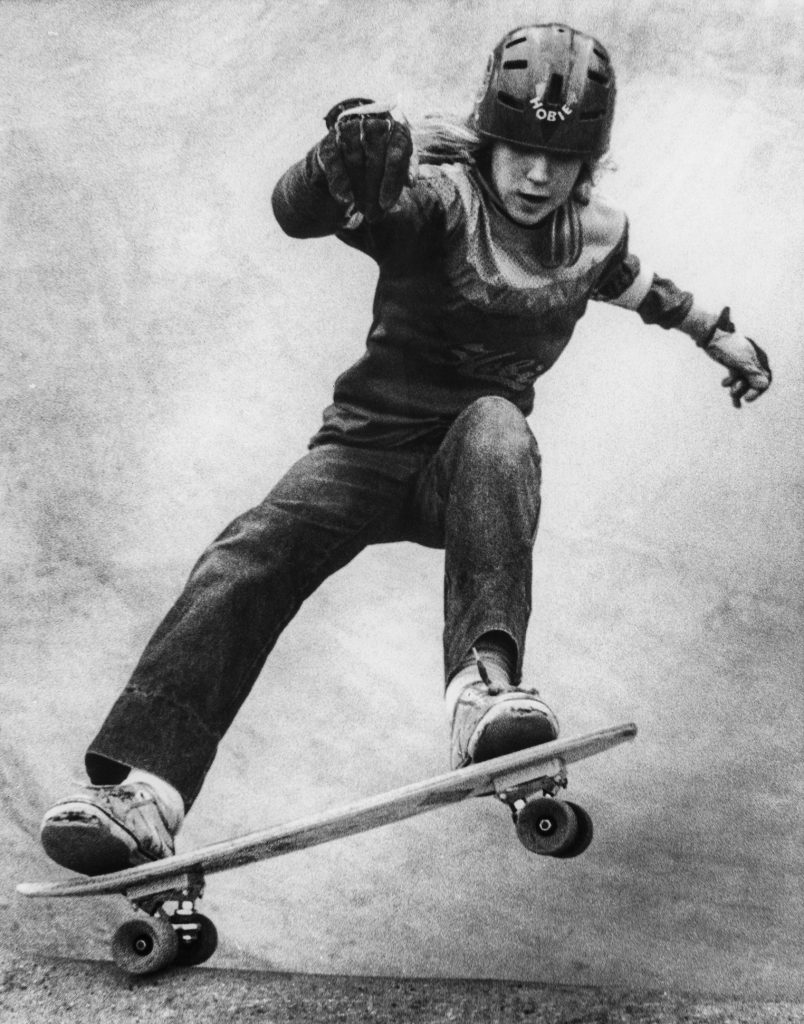

Skateboarders themselves are also becoming much more diverse. Although females were prominent in the 1960s and 1970s skate scenes – Patti McGee famously appeared on the cover of Life in 1965 – 1980s and 1990s street-based skateboarding was largely male dominated. By 2019, however, female riders are increasingly common, fuelled by female-only skatepark sessions and the way social media like Instagram makes participation more visible. Films like Skate Kitchen and the inclusion of skateboarding at the Tokyo 2020 and Paris 2024 Olympics – where men’s and women’s events will be given equal billing – will no doubt further strengthen this movement.

Skateboarders are also becoming more diverse in other ways. Always a meeting ground of different socio-economic backgrounds and ethnicities, skateboarding is finally embracing riders of different sexualities and identities, as exemplified by Skateism magazine and the 2018 Pushing Boarders symposium in London. Simultaneously, mainstream brands like Adidas, Nike and Selfridges are engaging with skateboarding, while in turn skate-based brands like Vans, Supreme and Palace are established high street favourites. And different types of riding – slalom, downhill, freestyle – continue to prosper alongside the more well-known street- and skatepark-based styles.

Today, then, skateboarding has matured into a plurality of locations, attitudes, riders, riding styles and cultures. While many urban managers still deploy “skatestopper” devices to deter skateboarders, more positive attitudes towards are emerging, as people become aware of skateboarding’s economic, cultural and health benefits. In cities such as Coventry, Hull and London – just as in Bordeaux, Brisbane and Malmö – there is substantial public support for skateparks, skateable public spaces, skate-focused schools and skate-friendly city policy. It seems as though skateboarding is finally being seen in its true light: at once critical and caring, rebellious and entrepreneurial, non-conformist and mainstream, and so as a dynamic presence in cities worldwide.

Iain Borden is an architectural historian and urban commentator. He is currently Vice-Dean Education at The Bartlett, University College London, and Professor of Architecture and Urban Culture. He wrote Skateboarding and the City: a Complete History on the link between urban spaces and skateboarding.

This essay was curated by The Subcultures Network, which was formed in 2011 to facilitate research on youth cultures and social change, and commissioned as part of the National Lottery Heritage Funded project to build the online Museum of Youth Culture. Being developed by YOUTH CLUB, the Museum of Youth Culture is a new destination dedicated to celebrating 100 years of youth culture history through photographs, ephemera and stories.

The National Lottery Heritage Fund invests money to help people across the UK explore, enjoy and protect the heritage they care about - from the archaeology under our feet to the historic parks and buildings we love, from precious memories and collections to rare wildlife.

Have a Read

Trasher

R.A.D. (Read and Destroy)

Concussion

Skateism

Turn On

Gleaming the Cube, Graeme Clifford, 1988

Video Days, Spike Jonze, 1991

Skate Kitchen, Crystal Moselle, 2018