Space Is The Place

A Conversation with Kieran Yates & Emma Warren

Writers Kieran Yates and Emma Warren have known each other for years and have shared a number of different powerful spaces – as friends, colleagues and dancefloor thinkers. Their books ‘All The Houses I’ve Ever Lived In’ and ‘Dance Your Way Home’ place a central importance on space and youth, looking at these interlocking subjects from different perspectives. Their conversation covers front room shubeens, listening to music on park benches in the city and in the countryside, and asks who’s really being antisocial when they shut down communal spaces.

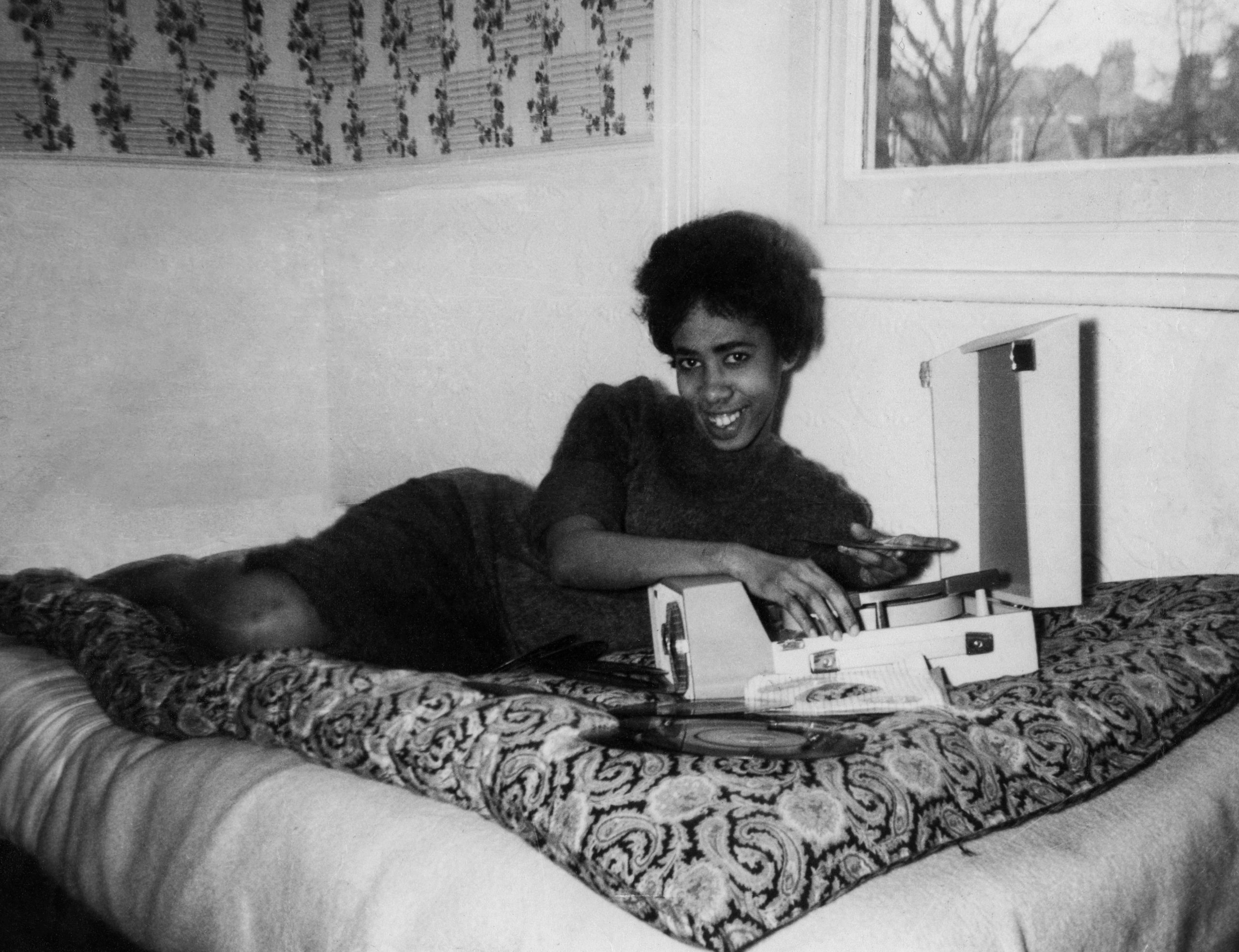

Kieran Yates and Emma Warren | Cover Photo Rosie Bond | 04.07.23

Emma Warren: There’s a very joyful and youthful energy in your writing. Is that intentional?

Kieran Yates: We know that moving around a lot can be really funny. The unassuming, unexpected friendships you make can be joyous and can open up new worlds for you. Sometimes you meet them on the dancefloor, sometimes in someone’s bedroom. My book is a documentation of all of those little homes that people have opened up for me and I’ve tried to open up for them, while there are these pressures on you, maybe like your rent going up. Sharing space in a tent or someone’s bedroom, playing Massive Attack or Chemical Brothers or Limp Bizkit. That creates a specific and joyful kind of connection with people. It’s about the music we bring with us, and it’s those cultural experiences we bring with us to inspire other people.

EW: That thing about opening up new worlds in shared spaces really resonates with what I’ve done in my book. You’re saying that home is more than a house; it’s the sanctuary you build with the spaces you can find. It broadens out the idea of home. I’m trying to expand the dancefloor away from the rave, which is conflated with drugs and hedonism and things the state wants to control, and into shared spaces where we move to music. For me, the dancefloor is a family front room, a school disco, the village green, the crossroads where ordinary people have gathered to dance for thousands of years. It’s really normal, and really communal. It can’t be squashed into one place. Everyone needs it, but young people need it especially – because it’s partly a way of finding out who you are.

KY: You can live a life on the dancefloor...

EW: Writing the book really made me realise that the dancefloor is a portal and that’s partly because of the material upon which we dance. There’s a bit in my book about 1930s Ireland, and my maternal grandmother who left Ireland as a teenager. I understood something new about how the Irish in London danced with and for their loved ones back in Ballybeg or Borisokane. They were in spaces that looked similar, listening to the same or similar music. You’d have these hits – say, Count Basie’s Doggin’ Around – being danced to at The Atlantic in Waterford and at The Forum in north London and similar places in Chicago, where many Irish people went. Stamping out that connection because of the way the dancefloor can transmit and receive all that material that’s being sent out, in different parts of the world.

KY: I love that idea of receiving something and absorbing cultural dance memory. I was touched by some of the stories of the literal residue of the waist high mark on a wall where people were dancing the rub-a-dub, the scrape of a belt or the indigo of your jeans and it leads you to think about the literal thickness of a wall and how that facilitates sound. Or an offhand remark someone made to me about retreating to the home in the face of racist door policies. I said: ‘how did it feel private, did you have thick curtains?’ and they said: ‘Oh no, the condensation did all that’.

EW: That’s lovely. There’s a little bit of rub-a-dub in both our books and the way people would make the dancefloor at home if you weren’t welcome elsewhere.

KY: When I was on a council estate, I was hearing music through the walls. I knew I liked it, but I didn’t know what it was. You navigate that as a student, hearing music I’d never have heard otherwise. Some of it was terrible but I learned so much from just hearing it. Then with flatmates, I was hearing their taste through the walls. They were doing an informal selector job. I’d go in and ask what it was when I liked it – or when I didn’t. We found unintended uses. Will Chicago house scare away the mice? Industrial German techno did.

EW: You’ve just reminded me of moving into a flat in Hulme in Manchester in the late ‘90s. When I moved in there was a lot of very loud, great music coming from the flat below. I remember thinking straight away ‘I need to also make my mark musically. I need to let you know that I’ll be playing music too.’ I felt like me and my downstairs neighbour were introducing ourselves through the floorboards.

KY: A bit of a soundclash.

EW: Yep. I wanted to ask you something else. You’ve got the experience of living in the countryside and in the city. What did that allow you to understand about any difference or similarities that rural kids and city kids want and need?

KY: In my experience there was a greater accessibility to internal and external space in the countryside. A lot of the housing stock was cottages or very study Victorian homes that I spent time in as a teenager. You could play music in that room without bothering the mum downstairs. It felt like such a new idea for me. The teenagers had complete agency over what was played, and I understood how that enabled them to take their music outside. You’d find a shed in a field, and this becomes a place where you can take some music and sit around and chat. There was this almost entrepreneurial thing in Year 9 where the Year 11s would put on barn dances or parties in the local Town Hall. They’d play guitar music, maybe there’d be a local DJ, but the crucial detail about it was that these were unchaperoned spaces. It felt so unencumbered by adult presence. I was like ‘wow, I didn’t know you could do that’. When I moved back to London, I was like ‘you know we could go to the park and play music and not feel antisocial?’ which is a deliberate use of the word. Young people have that accusation levelled at them, that they’re antisocial but it’s such an arbitrary way to be policed. You can be criminalised just for sitting in the park playing music. It feels more and more radical every day. It felt radical when I was 16.

EW: That absence of unchaperoned space is mad, and quite dangerous. Young people need space where they can look out for themselves, where there are adults available but not policing the space.

KY: You and I have previous lives as music journalists, so we’ve had a really unique connection to the way antisocial behaviour has been used and enforced on people. I don’t think you can think about landlords using that term to evict tenants in 2023 without thinking about how that was used around wearing hoodies in the club. That has musical roots. It’s part of a larger ecosystem.

EW: I think that it’s good that you and I are using the word ‘antisocial’ in new ways. It’s antisocial to complain about noise. It’s antisocial to raise rents when you don’t need to. It’s antisocial to tell kids to turn music off in the park. I think we should be giving that phrase to different sectors of society. When I think about ASBOs I think about Slimzee being banned from going above the fourth or fifth floor of a block. On one hand it’s seen as funny but on the other hand, he couldn’t go and see his grandma. It’s become a byword for something comic but it wasn’t funny for him, at all. There was a dubstep crew Antisocial Entertainment – Quest, Heny G, Silkie – back in the mid-2000s, appropriating the word for themselves. We’re saying it now: you’re looking in the wrong place for antisocial behaviour. I think our reporting on music allows us to see a lot of this material as cultural as opposed to being social or about charity. Your Radio 4 documentary Estate Music did a really good job of applying language and framework to something which had no language or framework around it before.

KY: Once you demonise place you demonise cultural production as well. Sampling Whatsapp voicenotes, or writing songs about your Blackberry, or sampling the acoustics of a stairwell on the estate – that all came from a very particular Black British music culture, and it took the mainstream a long time to recognise that at all. The relationship with new tech, the way you use your phone, the acoustics, being part of the tracksuit mafia where you wear soft clothes in hard spaces, it’s so rich and it tells us so much about how we live. A lot of that education is coming from young people.

EW: That is the key thing. I think both of us believe – know – that young people contribute massively to society, just by their very presence. By the fact they’re innovators. They’re having to live in the world before we are. They’re already grappling with things that will later affect more people.

"Young people have that accusation levelled at them, that they’re antisocial but it’s such an arbitrary way to be policed. You can be criminalised just for sitting in the park playing music. It feels more and more radical every day. It felt radical when I was 16." - Kieran Yates

KY: One of the things I loved about your book is what happens when we look at TikTok videos, young people providing us with joy through our phone screens. I’d love to hear you talk a bit more about the visual component.

EW: I think part of this is what myself and Elijah called an ‘optimism drop’. Part of the resistance against this ongoing narrative – it’s all hopeless, all the clubs have closed, it’s not like it used to be. It’s not optimism as cop out, it’s optimism as power up. Part of that for me is realising that teenagers and primary school age kids have so much dancing in their bodies. Kids know the difference between the ways your feet shuffle or Azonto. It points to a future that’s much more dance.

KY: I’m thinking of the videos circulating of Blue Ivy and her choreography as part of Beyoncé’s Renaissance tour. There’s something so powerful about seeing a very young person adopt that, to take it on, and to inspire a generation to take a couple of moves from that.

EW: It’s joyful to see that passing on that knowledge from mother and child but also that passing on skill from young person upwards: ‘here I am, as a person, not just someone’s kid’. I thought that was really striking.

KY: If you were to dance your story now I’d know how you were feeling. The amount to which I extend my arms expresses where I am in my head. If it’s a long full on arm extension, I’m happy. It reminds me of the way that small things, like being in a dark space or not having cameras, really makes a huge impact for lots of communities. Say in South Asian communities where you can only express yourself in this way under cover of darkness – people who might have historically called that part of living a ‘brown double life’ – it’s like ‘Oh, I haven’t seen you dance like at a wedding’.

EW: I think questions about photographing people in the dance will eventually get pulled into a conversation about consent. The dancefloor is an intimate space.

KY: Does it spread the joy and keeps the joy level high? If it’s merely about marketing, maybe that comes with a different energy.

EW: That makes me think about the painter Denzil Forrester who’d paint Shaka dances in the late 1970s and early 1980s. I asked him if he ever crossed paths with the dancefloor photographers from the same time. He said no and said something like ‘I’m not sure I approve of that’. He knew how much precious life material was being expressed and processed and it was not appropriate to freeze that moment through a machine. Some people didn’t even want to be drawn.

KY: The idea we can only retrieve the archive from, say, club photography, is not true. For me as a writer it’s about drawing on that from my memory and imagination and then documenting it.

EW: In terms of your work, what do you want people to do around spaces for young people?

KY: It’s about documenting and building community. Something like Daytimers, young people who come from a history of having daytime raves, but how does it relate to our lives now? How do we write about it, document it, then find space to see if it works now? It worked. Documenting and reflecting shows you’re not alone in wanting this kind of space, in recognising how important it is, or in knowing that it can bring you together. Sometimes it’s hard to see the connection between writing and this amazing club space or this amazing party but all these things are connected.

EW: I want to make it normal for young people to have house parties, either in houses or other spaces. I want someone to do some work with councils so they have strategies to deal with the imbalance where person can complain and stop the music for 300 people. I want anyone who can to run under-18s night. I know it’s difficult, but I think it’s possible to co-curate U18s nights with young people or to make it possible for them to run their own nights and I just want to see it.

All The Houses I’ve Ever Lived In by Kieran Yates

Dance Your Way Home by Emma Warren