The Everlasting Tale of The Teenage Outsider

Words by Anna Doble author of Connection Is A Song | 15.05.24

Before the internet, and the infinite brain-defrag of social media, it felt like a huge deal any time you met someone who liked the same band as you. This sensation of instant connection didn’t have to be particularly niche; I’m not talking about unreleased Boards of Canada demos, I’m thinking of one joyful moment when a woman on the bus in Leeds nodded appreciation at the sound of Primal Scream trickling from my orange foam headphones. I’m also recalling the boy in art college who used to lean over the top of my easel to sing The Smiths’ "I am the son and the heir of a shyness that is criminally vulgaaaar...” before returning to his charcoal drawing of a woman called Rosie.

From the birth of the teenage concept in the 1950s (Coca Cola! Rock ‘n’ roll! Jeans!) until my career as a teen in the 1990s (Global Hypercolor! Hooch! Britpop!), the true point of it all was to have as much cheap fun as possible while railing against your parents, your teachers and the shopkeeper who stopped you from flicking through Smash Hits until you’d bought a copy. The teenager was programmed to chew gum noisily and to mess with their hair for way too long in the bathroom mirror. They were spotty and moody and stayed in bed until midday. But beyond all this the main aim of the game, back then, and for a long while, was to feel like an outsider. Is there such a feeling now in an era of hyper communication? Is it in fact an experience that gets stronger because of the digital noise that we all must tolerate? I fear that listening to The Holy Bible by the Manic Street Preachers while gazing from the window has been replaced, for modern teens, by the sensation of staring at a screen in a state of permanent #fomo.

My story is about being a kid on the outside during the 1990s and that’s the tale I tell in Connection is a Song: Coming Up and Coming Out Through the Music of the ‘90s. I was literally outside, a lot, in that era; hanging an arm from the half open door of my friend Yorkie’s blue Mini Cooper while listening forlornly to Radiohead singing (well, of course) about feeling exterior. We’d spend hours in country lanes, under hopeful UFO moonlight at Brimham Rocks, on the rails of a carpark grinding an ollie while sipping from a warm bottle of Becks. I looked too young, you see, until I was well into my 20s and so we had to continue doing actual young things. And being youthful in a provincial town brings twin terrors. Terror One: You will be turned away at the bar, and not only will you have to leave but all your friends will be ejected too. Your own night ending in the Esso garage with a bag of Doritos is one thing, your whole tribe forced to trudge off into the cold is mortification itself. Terror Two: This one only applies to females in smalltown nightclubs. It’s the predatory man who, in the ‘90s in the north of England, was often called Gareth or Craig. He wants to buy you a Bacardi Breezer. Do not let him.

Aside from these perils, was there a better time than the 1990s to fall in love with music? When I look at the ticket stubs, mixtapes and stickers that form the detritus of my youth, I think to myself that I was very lucky indeed. Across every genre there was innovation. I found myself falling for indie and pop and drum ‘n’ bass and weird electronica and trip hop and pastoral rave, pretty much in the same fortnight. My Little Fluffy Clouds tasted of Eternal 3 A.Ms and my Parklife was Too Young to Die.

Most tales about the music of the ‘90s are set in The Good Mixer (Camden’s famed indie band pub, where Menswear would pot the black too soon) or the Groucho Club, somewhere between Liam Gallagher’s monobrow and Alex from Blur’s 20 bottles of Veuve Clicquot. Connection is a Song is not that story. It is a tale of my decade, and how it connected me to the people and places of my future. I wasn’t sick of Britpop by 1996 like the bands of the era often say they were and I wasn’t losing my mind in a blizzard of cocaine, as one infamous cover of Select magazine once declared about the one-time heroes of UK indie music.

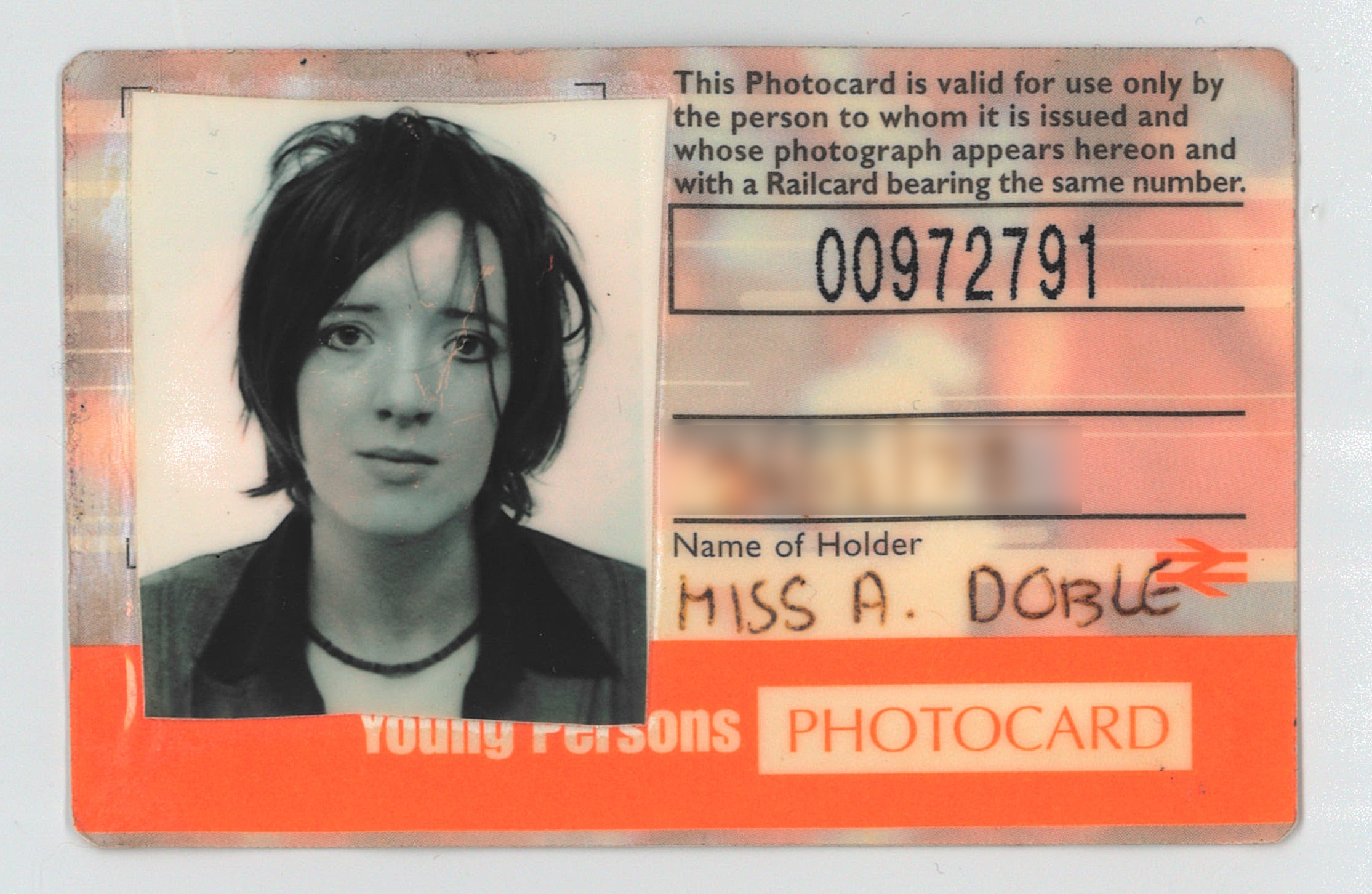

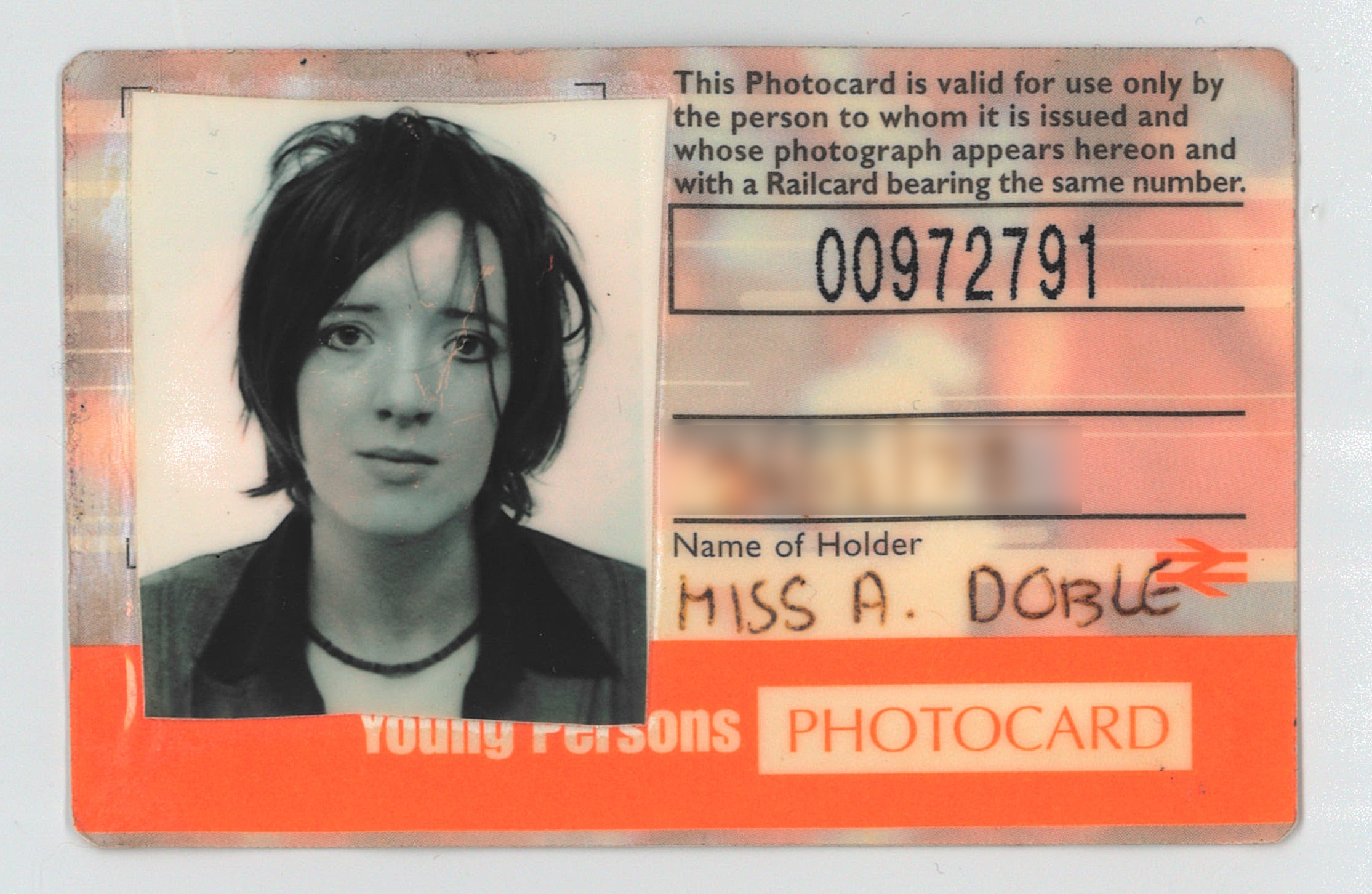

In that same time I was excited and hopeful and staring at the stars from my loft window in a small Yorkshire town called Knaresborough. In the photo above you see me in my late teens after an attempt at getting "Elastica hair". This mission, which went on into my 20s and 30s, and some might say still persists, was forever thwarted by my naturally curly locks. One of my friends had a perfect yet accidental Britpop fringe which seemed unfair to me when it was me making all the effort, studying the NME weekly and investing in hair wax. I wanted to be slick and angular like Justine Frischmann adjusting her microphone stand. In reality I was a chubby-cheeked teen waiting for my time.

I hope that reading my story will take you back to the rollicking guilt-free decade you may have lived yourself, or heard about. It is certainly very ’90s by the end when I am nicking Moby’s beers and waking up in post-rave woodlands with a grin on my face. Mostly I am just a girl trying to build something to believe in from Just 17 stickers and scraps of paper stuck onto peeling walls. If you grew up in a provincial town with one terrible nightclub, I am probably you. If you looked too young to get into a pub until you were well over 18, then I am definitely you.

Connection is a Song follows me from the sunny, hopeful days of early 1990, via the tissuey thinness, yet forever evocative ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ (the Candy Flip version), through to the joyous days of Italia ’90 and a New Order summer that will, of course, end in tears. I grow up a little, but not much, and listen to East 17’s ‘Deep’ on a loop while covertly smoking from my friend Lisa’s window ledge. Later I faint while watching the Manics and come round to find myself covered in black feathers.

The point is that in this book I am very probably you. This is the story of provincial and suburban life: dreams of glamour and danger kept neatly in card boxes; secret crushes kept hidden in code; haircuts acquired via a woman on the high street called Tracy. This is the story of pop music in the ’90s from the viewpoint of the unjaded fan, and one who often felt alone, waiting for fanzines to arrive in the post while saving up for far-off music festivals.

You might argue that the TikTok age of the micro-niche has, in fact, changed things for the teen outsider. Now you can find your tribe, without moving from the sofa, via a series of addictive upward swipes. The Spotify playlist (or perhaps the dark energy of a Spotify Blend) has muscled in where once the carefully crafted cassette reigned over our tender hearts. The endless smartphone selfies are the Woolworths photo booth without the choice of nylon curtains. But I suspect the instantaneousness of it all makes moments of connection feel inevitable, rather than magical. I hope the magic persists but can the beautiful surprise of a shared musical love, and the weight of significance that carries, be fully transferred from the analogue to the digital world? I’ll never forget clocking the pile of seven-inch records belonging to my new friend Rose in the first week of university. Pulp, Blur, Gene and My Life Story – a mesmeric slam dunk that sealed a friendship that I cherish 25 year later. Of course, I made her a mixtape the very next day.