Coventry as a site of youth culture

from boomtown to the ghost town and beyond

Text by Rebecca Binns | 06.09.2022

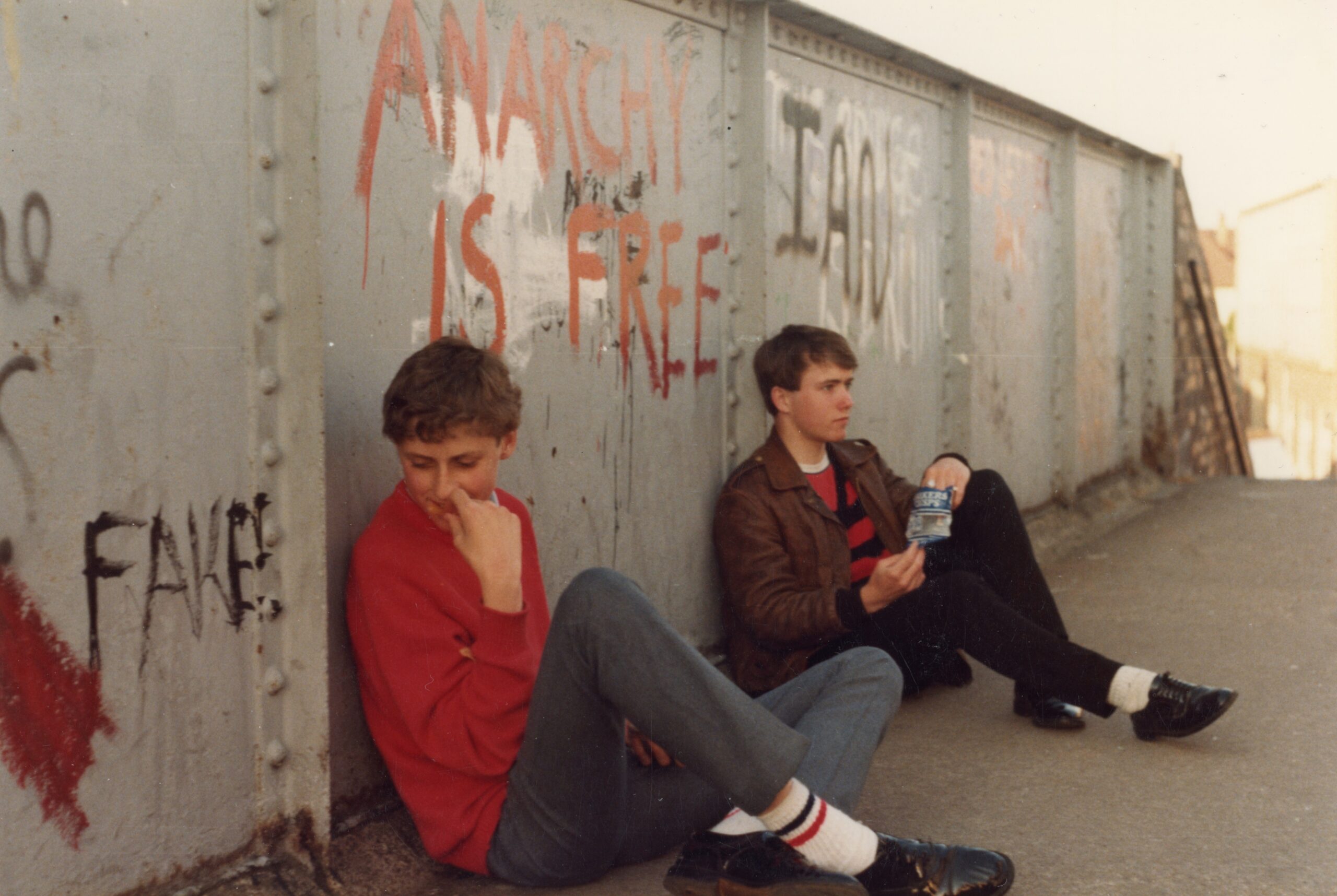

It’s ironic that the pedestrianised shopping precinct, symptomatic of the new, progressive vision for Coventry, following its annihilation from Luftwaffe attacks during WW11, came to be associated with neglect and inhospitality, as the place for various youth tribes in the late 1970s-early 1980s with nothing to do to hang out, and indulge in various toxic substances, petty crime and fighting. It was, however, this desolate image of the city that provided the impetus for Coventry’s most abiding contribution to youth culture, 2-Tone, the fusion of punk and ska that put the city firmly and indelibly on the subcultural map.

However, things had not always been this way. Even The Specials’ song Ghost Town (1981), their anthem to their beleaguered city, opens with the lines,

Do you remember the good old days, before the Ghost Town

We danced and sang and the music played at the boomtown.

For in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, Coventry had indeed been a boomtown. Attracted by high levels of employment, the Coventry of the post-war years had a higher proportion of people under 25 than the national average. Young people, fresh from jobs in the automotive industry, congregated at youth clubs and discos held in church halls and community centres. In 1960, The Locarno Ballroom, run by the vast Mecca Leisure Group, became the locus for mainstream entertainment. Focusing on ‘big band’ shows and orchestras, the chain generally shunned anything new, or different, in the fear that it would not provide enough of a draw. The Locarno also hosted alcohol free disco nights for teenagers on Tuesdays and DJ sessions for local office and shop workers at Friday lunchtime. Its Friday night disco played to packed crowds of over 2,000 people. This was all in synch with the wider trend among dance hall operators to balance the demand for ballroom style dance orchestras with demand from younger audiences for popular music.

However, this era also saw a shift away from the larger mainstream venues towards more informal places, featuring modern jazz inspired by artists like Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker. Coventry had a thriving jazz scene from the 1950s to the 70s, centred on The Mercer’s Arms pub, while in the 1960s it also featured R&B. The sharp suited/mini skirted Mods often gathered around jazz scenes such as this.

Skiffle, Britain’s home grown hybrid of rock n roll, blues and folk, influenced by the likes of American folk singer-songwriter Woody Guthrie, also had a notable presence in Coventry. The Coventry Arts Umbrella Club (opened by The Goons in 1955) hosted a folk club, alongside numerous Coventry bands and literary figures such as the poet Phillip Larkin, which fed into the city’s wider folk scene during the 1960s.

The demand for alternative music venues throughout the UK also came from within West Indian communities, arising as much from necessity as want, due to the discrimination they often faced in mainstream venues. Alongside attracting a young, white, working class demographic, Coventry’s success also made it a locus for immigration, primarily from the Commonwealth. While the majority of migrants hailed from the Indian subcontinent, it was primarily self-organised Jamaican communities that influenced the nightlife scene in postwar Coventry. They introduced sound systems that were comprised of DJs playing vinyl on decks that were rigged up to vast speakers at ‘blues’ house parties, in community halls and centres, or in outdoor spaces. Coventry’s Police Ballroom also hosted early ska and reggae events, while bands such as The Pioneers and The Upsetters performed at the Chesford Grange (both in December, 1969). The Coventry jazz singer Ray King (an immigrant from the Caribbean island of St Vincent) had success nationwide with a series of bands built around his soulful vocals. He later became a formative influence on 2-Tone.

As the 60s rolled on, Coventry was affected less than a lot of places by the changing youth culture of the day. In the wake of Paris 68,’ student politics became more militant, and there was widespread activism, protests and sit-ins in universities, colleges and art schools around the country. The proximity of Warwick University, characterised by its radicalism, to Coventry meant an overspill of hippies, intellectuals and political activists in the wider area. Nearby Birmingham has been recounted for its ‘freak’ scene, centred on Whiskey on Navigation St and The Elbow Room in Aston. However, despite the creeping commercial viability of the counterculture, in many places, including Coventry, hippies remained in the minority.

Jazz and folk remained strong throughout the early 1970s at venues like the Mercers Arms pub, which also hosted discos. Around this time The Locarno hosted a range of major rock outfits, including The Who, Pink Floyd, Slade, Hawkwind, Led Zeppelin and ACDC. Many of these bands, including Black Sabbath and Zeppelin’s Robert Plant, hailed from the West Midlands, which became the hub of the emergent Hard Rock scene. The Lanchester Polytechnic (which became Coventry University) served as another popular venue, holding the Lanchester Arts Festival, which hosted the inaugural performance of Monty Python’s Flying Circus in 1969. Chuck Berry wowed the audience there in 1972, at a show that also featured the debut of Wolverhampton rockers Slade.

The Poly then played a role in the birth of the new youth revolution when it hosted a live show featuring Sex Pistols and The Clash in 1977. However, according to Horace Panter of The Specials, this near legendary show was poorly attended. Despite it being something of a damp squib, Panter acknowledges ‘the punk rock revolution hit hard in Coventry,’ inspiring thriving punk and post-punk scenes as well as 2-Tone itself.

So much is made of punk that it’s easy to forget that most people in the late 1970s enjoyed the escapism provided by nightclubbing; the popularity of soul, pop and disco as the staple sounds being a case in point. Clubs were largely aimed at an aspirational clientele, and dress codes requiring women in ‘feminine’ attire and men in suits and ties were often enforced. For early adopters of the punk rock revolution, this meant maintaining a low profile (hard given the consciously provocative dress code) was essential to avoid being the target of abuse and violence. The only pub to allow punks entry was a gay pub, The Rose and Crown (the High Street). But reflecting the dominant mindset of the time, this led to them being further targeted by association. Nevertheless, the punk scene rapidly gained traction, resulting in more venues opening their doors to this burgeoning demographic.

A wide and eclectic range of smaller venues, including pubs, colleges, community centres, theatres and outdoors festivals, hosted punk and post-punk bands and DJs as the scene evolved. The Locarno, which changed its name to Tiffany’s on 14th February, 1974, was quick to adapt to punk, as it became mainstream from around 1978, featuring The Clash, Blondie, The Undertones and The Stranglers. 1979 also saw the venue host a gig by two local acts made good. Fresh from the release of their eponymous first album, The Specials headlined a show that also featured the recently formed band The Selecter.

The economic problems which affected Britain during the 1970s were felt more keenly in Coventry. In the early 1970s, there had been the highest percentage of people in work in factories in the whole of Europe. It was also the highpoint for militant socialist, trade union activity, with huge strikes and demonstrations held in the area. As the 1970s progressed, mass redundancies occurred as factories downsized or closed, largely due to competition from abroad as the car industry became more international. Unemployment then soared during Thatcher’s first term in power (1979-83), disproportionately affecting the young and working class. The first 2-Tone single (Gangsters/The Selecter, by The Specials/The Selecter) and the first album by The Specials released in October, reached prominence in the immediate aftermath of this decisive election.

2-Tone, which inherited the speed and aggression of punk, combined with the infectious rhythm of ska, crossed racial and other divides. Both The Specials and The Selecter included black and white members, who also spanned the city’s class divide. A short lived phenomenon given its continued influence, 2-Tone was notable for providing social comment that was both intelligent and unpretentious, and which reflected young people’s experiences. Songs are riven with a sense of young lives blighted by the threat of violence, bleak prospects and small mindedness; amidst the desolate setting of a harsh urban environment. As The Specials’ songwriter and lead guitarist Rod Byers (aka Roddy Radiation) wrote in the opening verse of Concrete Jungle:

I have to carry a knife/Because the people keep threatening my life

I can’t dress just the way I want/I’m being chased by the National Front

Concrete jungle, animals are after me/Concrete jungle, it ain’t safe on the streets

Concrete jungle, glad I’ve got my mates with me

The optimism and political consensus of the post-war decades had given way to something a lot less promising. But, like punk, 2-Tone itself was exciting and revitalising. Its message was upbeat, progressive and anti-racist. The dominant youth culture among Coventry’s white working class youth at the time was not punk, but skinhead, which points to the confused relationship between the bands and their supporters. While skinhead had originated as a niche movement of aficionados of Jamaican ska and reggae, by the late 1970s the National Front had infiltrated the younger scene to some extent. By contrast, 2-Tone’s message was one of solidarity in place of antagonism among youth subcultures. The bands continued the trend in punk to break down notions of performers as stars, separated from their audiences. Instead, kids in the audience would often be hauled on, or invade the stage, sometimes in droves.

It would be a mistake, however, to see 2-Tone as all encompassing, and Coventry hosted a thriving post-punk scene at the time. Post punk icon Hazel O’Connor’s father had been part of the wave of Irish migrants who came to the city in the post war years. Alan Rider, who produced the Coventry fanzine Adventures in Reality (1980-85), which covered the emerging anarcho-punk genre and was notable for its confrontational presentation and coverage, recalls a scene that had taken off since its earlier punk incarnation, embracing what he saw to be its true DiY spirit. A wide range of smaller venues now hosted a vast array of punk and post-punk bands alongside the larger ones. As well as the downstairs bar at the Lanchester Polytechnic, this included the Belgrade Theatre Studio, The Bear Inn, The Godiva, Swanswell Tavern, The Zodiac, The Hope and Anchor (which also hosted Al Jones’ punk Cocaine Disco), the Dog and Trumpet, The Hand and Heart, Mr Georges, The Heath Hotel, The Plough, The Climax, The General Wolfe, Matrix Hall and Butts College, which all hosted local and touring bands in a lively scene. Local acts included Squad, Criminal Class and Homicide, The Wild Boys, Urge, Eyeless in Gaza, V Babies, Clique, Monachy (their spelling!) and Protégé.

Grindcore pioneers Napalm Death, from the village of Meriden near Coventry, were formed by Nick Bullen and Miles Ratledge in 1981, while the duo were still in their early teenage years. An early vocalist with the band, Lee Dorrian went on to form doom-metal band, Cathedral. Death metal and grindcore band Bolt Thrower (1986) also came from Coventry. The exciting, ‘anyone can do it’ ethos that characterised the wider post-punk scene echoed the energy of 2-Tone, and similarly favoured independent production of both records and fanzines over mainstream publications.

Despite all this positive energy, racist attacks on Black and Asian communities throughout the UK were on the rise. In Coventry there were petrol bombings of homes and places of social gathering. In 1981, 20-year-old Satnam Singh Gill was stabbed to death by two white teenagers. This followed the racist murder of the Asian doctor, Amal Dharry, who was stabbed to death by a 17 year old skinhead, for a £15 bet to ‘get a p*cki that night.’ This occurred outside a chip shop that was local to The Specials’ founder, chief songwriter and keyboard player (who also founded the independent label, 2 Tone Records) Jerry Dammers. Dammers helped to organise a benefit concert at the nearby Butts Stadium in response in June, 1981. Local left wing and anti-racist groups banded together to counter the threat, and the resultant Coventry Committee Against Racism (CCAR) encompassed over 40 organisations, including the Anti-Nazi League and Indian Workers Association. If 2-Tone saw a mixing of black and white youth, these more political movements also saw engagement from the South Asian community. It was from this community that Coventry’s next seismic contribution to British youth culture would emanate, with the development of Bhangra.

While there were significant Sylheti and Gujarati communities in Coventry, the majority of South Asian immigrants came from the Punjab region, an area in the North of India that spans the border with Pakistan. While Muslim and Hindu Punjabis migrated to the city, there was an unusually high proportion of Sikh immigrants, and it was from this community that Bhangra came. Originally a Punjabi music and dance tradition, Bhangra featured prominently in community affairs, with bands earning a healthy living playing weddings and community events. The kids of first generation immigrants, who grew up listening to their parents’ music, then fused it with contemporary western influences, but in a way that assimilated rather than allowed itself to be assimilated. In the 1980s British Bhangra crossed over from its identification with the traditional, folk music form, to a multi-faceted genre that permeated the British nightclub scene.

Coventry artist, Silinder Pardesi, formed a well rated British Asian Bhangra band, 'The Pardesi Music Machine,’ in the early 1980s, which fused Punjabi and Hindi music with influences taken from reggae, dance and R&B. Their first Bhangra album 'Nashay Diye Band Botlay' followed in 1987, but it was their second album, ‘Pump Up The Bhangra’ (1988) that proved a major breakthrough in British Asian music, shifting major volumes and reaching well beyond the Asian diaspora.

Simultaneously, Coventry was at the centre of the house music ‘revolution,’ which was focused at the club, Eclipse, which launched in 1990. People involved with the scene have described it embodying a great coming together of people from divergent class and racial background, representing a grassroots, and socially progressive form of hedonistic transgression. The Dome in Birmingham hosted all day Bhangra parties, also known as daytimers, which proved a huge hit with local South Asian youth. In Coventry, there was a South Asian movement going to these daytimers, but there were also children of first generation migrants immersing themselves in the rave and Hip-Hop scene. DJ and youth culture archivist Hardish Virk, whose father had been involved in the Indian Workers Association, was typical of this new generation, recollecting,

My starting point was the Coventry rave scene and being a DJ playing hip hop at events I produced and promoted. The audience at The Dome didn’t really connect with the rave and hip hop scene that I was part of as it was mainly white and black young people.

One particularly prominent Coventry artist was Panjabi MC, whose focus is on combining Bhangra with hip hop Although he started performing in 1993, he is best known for his song, ‘Mundian To Bach Ke’ (Beware of The Boys), 2003, which sold over ten million copies worldwide.

This mixing of previously distinct genres and music from separate cultures is perhaps what defines Coventry. Coventry born Clint Mansell’s band, Pop Will Eat Itself, for example, imbued the same hip hop and rave culture as the city’s Asian youth, which led to the band moving from their indie roots to a sound that encompassed samples, loops and beats. Perhaps, though it is Tim Strickland, the first, if short lived, vocalist for The Specials who said it best.

Everyone in Coventry is an outsider, there’s no such thing as a Coventry person: anything innovative has had to come from the outside.

This article was published as part of Amplified Voices: Turning Up the Volume on Regional Youth Culture. With thanks to National Lottery Players and the ongoing support of the National Lottery Heritage Fund.