Football is everywhere these days, in high-end stadiums, on the telly and permeating every area of our culture. But this has been a major shift since the 70s and 80s, when football was mainly the preoccupation of working class Brits. It is in these days that teenage, fashion-forward football fans started filling the terraces - the Casuals. Delve into this youth tribe, from the fandom and fashions to the violence.

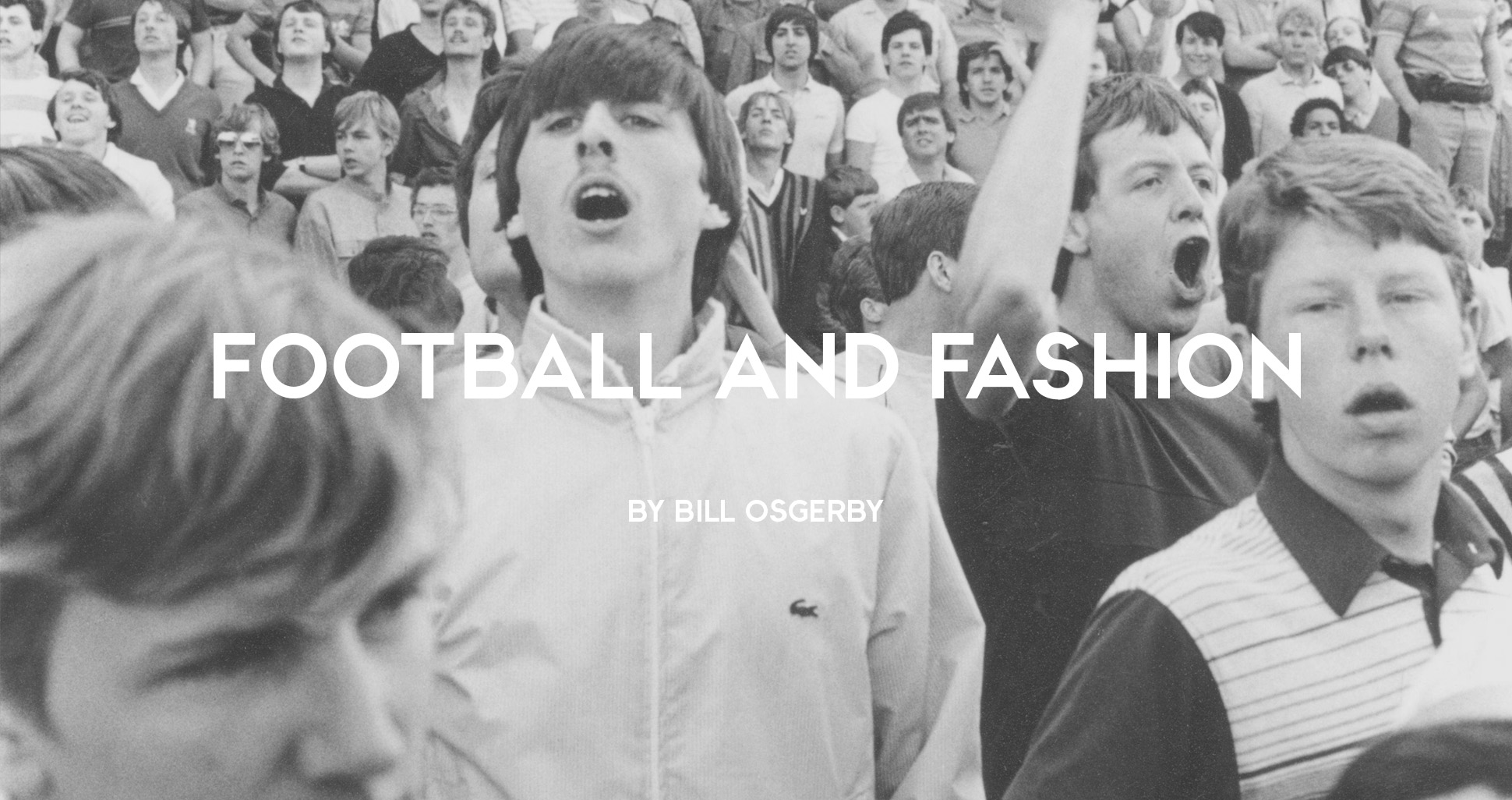

Text by Bill Osgerby, Cover Photo by John Ingledew.

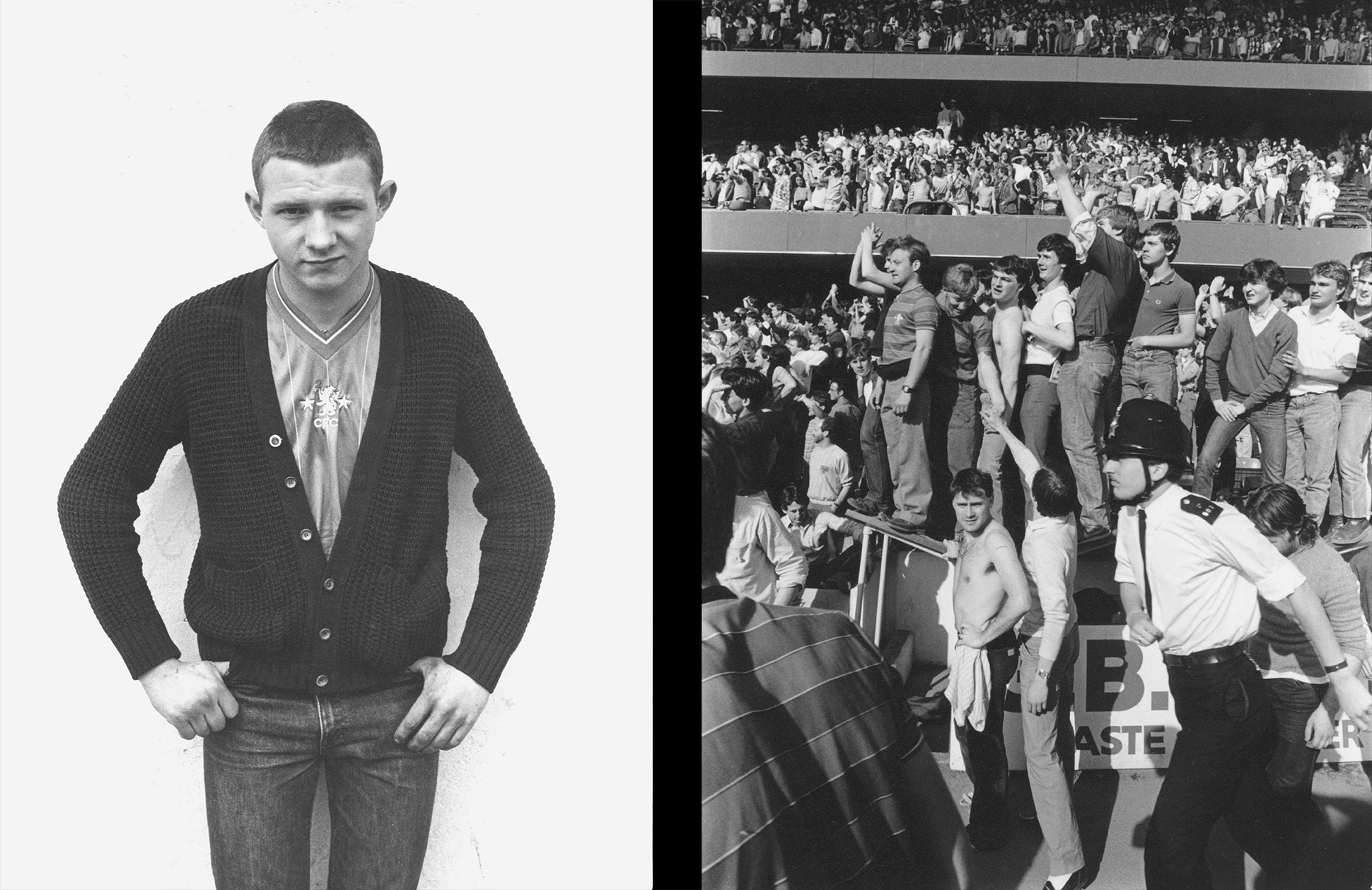

In 1985 the tabloid press drew attention to the appearance of the Cambridge ‘Main Firm’ − a group of Cambridge football supporters convicted of a violent attack on their Chelsea rivals. The Daily Mirror described the assailants as a ‘smartly dressed gang of thugs’ wearing ‘Pringle jumpers, denims and training shoes to make them look more like the boy next door than hooligans’. However, rather than being a cunning disguise as the Mirror intimated, the attire of the Cambridge Main Firm was indicative of the football-oriented ‘Casual’ style that had been crystallising in Britain’s working-class youth culture for several years. Observers noted a degree of regional variation in the Casual look, with corduroy flares making a comeback in Manchester, while Liverpool saw a vogue for baggy jumpers and sheepskin coats. There was also a dizzying turnover in fads and crazes. But, overall, the emphasis was towards a style that was smart and expensive, with a preference for Fred Perry sports shirts and Pringle golf jumpers increasingly giving way to an obsession with upmarket sportswear and high-class designer brands.

The Casuals, as they came to be known, evoked the sharp, competitive dress-sense of the 1960s mods. Some debate surrounds their origins, but there is general consensus that their roots lay in the British north-west during the late 1970s and early 1980s, where two parallel scenes paved the way for the Casuals’ development − the ‘Perry Boys’ in Manchester and Salford, and the ‘Scallies’ in Liverpool.

The Perry Boys − so-called because of their early proclivity for Fred Perry shirts − began to take shape in Manchester’s post-punk fallout of the late seventies and early eighties. Informed by the local Northern Soul heritage and the period’s mod revival, the ‘Perries’ affected a smart ‘soulboy-mod’ look. Alongside short-sleeved Fred Perry shirts, also de rigueur were Peter Werth long-sleeved, knitted polo shirts (often in burgundy or with thin hoops). Lee cords and Lois jeans were also much in evidence, together with Adidas sportswear − especially Adidas white, leather Stan Smith trainers. The haircut of choice tended to be a neatly combed ‘wedge’. Popularised by David Bowie on the cover of his 1977 Low album, the wedge had a long fringe, grown low in a ‘flick’ over one eye, with the sides shorter, layered and cut to a point at the back. Tastes in music were fairly eclectic, though soul and early synth-pop bands found some favour. Football was probably more important, and the Perry Boys competed on and off the terraces with their Merseyside rivals.

In Liverpool, the Perry Boys found their counterpart in the Scallies − a name derived from ‘scally’, local slang (abbreviated from ‘scallywag’) for a mischievous rascal. Scallies and Perries had some sartorial similarities but, by the end of the 1970s, the Liverpool lads were showing a distinct enthusiasm for European sportswear. During the late 1970s and early 1980s Liverpool FC enjoyed success in several European football competitions and their young fans, following the team across Europe, began returning home with expensive sportswear unavailable in Britain (some of it reputedly shoplifted from foreign stores). Items of Adidas and Lacoste clothing that were unavailable in the UK were especially prized, along with fashions from European labels previously little-known in Britain − for example, Sergio Tacchini, Fila, Ellesse and Kappa. Some inspiration was also taken from the Continental street fashions sported by groups such as the Italian Paninari − youngsters in Rome and Milan who coupled European sports brands with expensive American leisurewear.

""I was living in Battersea and you could hear the Chelsea crowd when a goal went in – so I started photographing the fans there. To take a camera along to a football game in the 70s was unusual. I’d get stopped by stewards and asked what I was doing. I had my Doc Martens boot laces taken off me, but never my camera." - John Ingledew, Football and Youth Culture Photographer

Bill Osgerby is an author and professor with a focus on modern American and British media and cultural history — with particular regard to the areas of gender, sexuality, youth culture, consumption, print media, popular television, film and music. Amongst other he has published, Youth in Britain Since 1945 and Biker: Style and Subculture on Hell’s Highway

This essay was curated by The Subcultures Network, which was formed in 2011 to facilitate research on youth cultures and social change, and commissioned as part of the National Lottery Heritage Funded project to build the online Museum of Youth Culture. Being developed by YOUTH CLUB, the Museum of Youth Culture is a new destination dedicated to celebrating 100 years of youth culture history through photographs, ephemera and stories.

The National Lottery Heritage Fund invests money to help people across the UK explore, enjoy and protect the heritage they care about - from the archaeology under our feet to the historic parks and buildings we love, from precious memories and collections to rare wildlife.