"Teenage youths roam the streets [...] and magistrates complain that their parents exert too little influence over their behaviour. The marvel of food technology makes it unnecessary for them to go home for their meals" Magnus Pyke - 1970

The thirty year period from 1970 to 2000 witnessed monumental and lasting changes to the way we eat in Britain. Those becoming teenagers at the start of the 70s were born into a society only recently recovered from wartime food rationing, and when kitchen appliances that we see as essential today, like fridges and microwaves, were rarely seen in British homes. Before the 1970s, eating out for pleasure was largely unheard of for the vast majority of the population. Although still a rare treat for most, technological, socio-economic, and political changes in this period led to the rise of fast food: quick and cheap food that could be eaten on the go. American fast food chains started to take root in the 1970s. Wimpy - serving hamburgers, fries, and milkshakes - first arrived in the 1950s, but by the 1980s had lost ground to McDonald’s, which opened its first UK restaurant in 1974 and reached a staggering 1000 outlets by 1999. Indian and Chinese restaurants also started to take off in this period, as British tastes widened in line with the increase in immigration and foreign holidays. As the historian and sociologist Derek J. Oddy wrote of food consumption in Britain, ‘from the 1970s until the end of the twentieth century change has been marked, not only in technology and processing but also in social patterns and behaviour’.

Another important social development following from the Second World War, was the emergence of youth culture as a distinctive entity, as the number of young people in the population expanded. Whilst we often associate these emerging youth groups with distinctive fashion, music, and dance movements, much less has been said on how the fast evolving food trends of this period related to youth experiences. Addressing this gap in scholarship, this article makes use of the Museum of Youth Culture’s rich collection of photographs that document the lives of young people across Britain. This is paired with a pool of over 150 responses to a survey collecting memories of fast food and youth culture from those who were teenagers and young adults in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s. It emerges that food - the tastes, smells, and sounds of eating - is particularly evocative of the events and memories of youth, and concurrently offers an engaging means of accessing wider historical trends. As sociologist Deborah Lupton has commented, ‘Commodities such as food act as “storehouses” of meaning, serving as reminders of events in one's personal past'. As I share some of these food memories - from mods eating Mr Whippy from an ice cream van, to teenagers hanging out at the local chip shop, or sharing a burger from fast food stalls at a music festival - I hope to illuminate the centrality of fast food to youth culture in the late twentieth century.

Google ‘fast food’ and ‘teenagers’ and you will be hit with a barrage of frenzied reports condemning the health and social implications of young people’s diets. Concerns about teenage obesity often accompany thinly veiled accusations of immoral behaviour. The Daily Mail ran a story in 2018 suggesting the police bribe teenagers with junk food in exchange for good behaviour, and the Sun reported that all under-18s were banned from a McDonald’s in 2016 after the behaviour of ‘anti-social yobs’ led to ‘discrimination that paints all teenagers with the same brush’. As part of a wider ‘Setting the Record Straight’ project, this article moves away from these generalisations and stereotypes surrounding young people by highlighting diverse experiences of fast food consumption.

jump to your favourite food using the buttons below

chips

“used to give a bag of scraps (bits of fried batter, scooped out of the fryer) for free. the chippy was the main option for fast food, and any unwanted chips could always be used to throw at friends.” John - Bolton, 1970s.

By the early part of the twentieth century, fish and chips - hot, cheap, and nutritious - had become Britain’s most popular ‘fast food’. It remained the takeaway of choice especially for the working classes until the 1960s, whilst one survey maintains that fish and chips still accounted for 43% of takeaways sold in 1981. My survey confirms fish and chips as the most popular fast food from 1970 to 2000, with an average over the decades of 52% of participants remembering eating fish and chips with some regularity (more than once a week to once a month), compared to 24% eating regularly at fast food chains, and 30% eating other takeaways like Indian and Chinese. Whereas for some, fish and chips was a regular meal at the family table, others remember push back from parents who hoped to maintain traditional values and to save money.

But the home wasn’t the only place that young people ate fish and chips. In 1971, an interview with Mr and Mrs Pratt, owners of Regal Fish Bar in Baguley, Greater Manchester, attributed the success of their business at least in part to being near three schools. A teenager in the 1980s in Ellesmere Port, Cheshire, David remembers sneaking a pie and chips for lunch on Fridays in Sixth Form ‘to avoid school dinners’. To John in Lancashire in the 1970s it was the ‘rough kids at school’ who would ‘bunk off for chips and curry sauce at lunchtime’. Fish and chip shops played an important part, then, in teenage rebellion, and young people who chose to eat in these establishments asserted their independence more broadly through food. Just as today, these fast food shops could also act as a social space for groups of youth, who met at fish and chip shops during breaks or after school. In London in the late 1980s, Amie remembers: ‘I didn't hang out with friends in my area much because it was a bit dangerous, and the kids who lingered round fast food chains and the chippy were frankly quite scary.’ This statement evidences the power of food and eating habits to create distinct social groups, with certain groups asserting symbolic ownership of the local fish and chip shop.

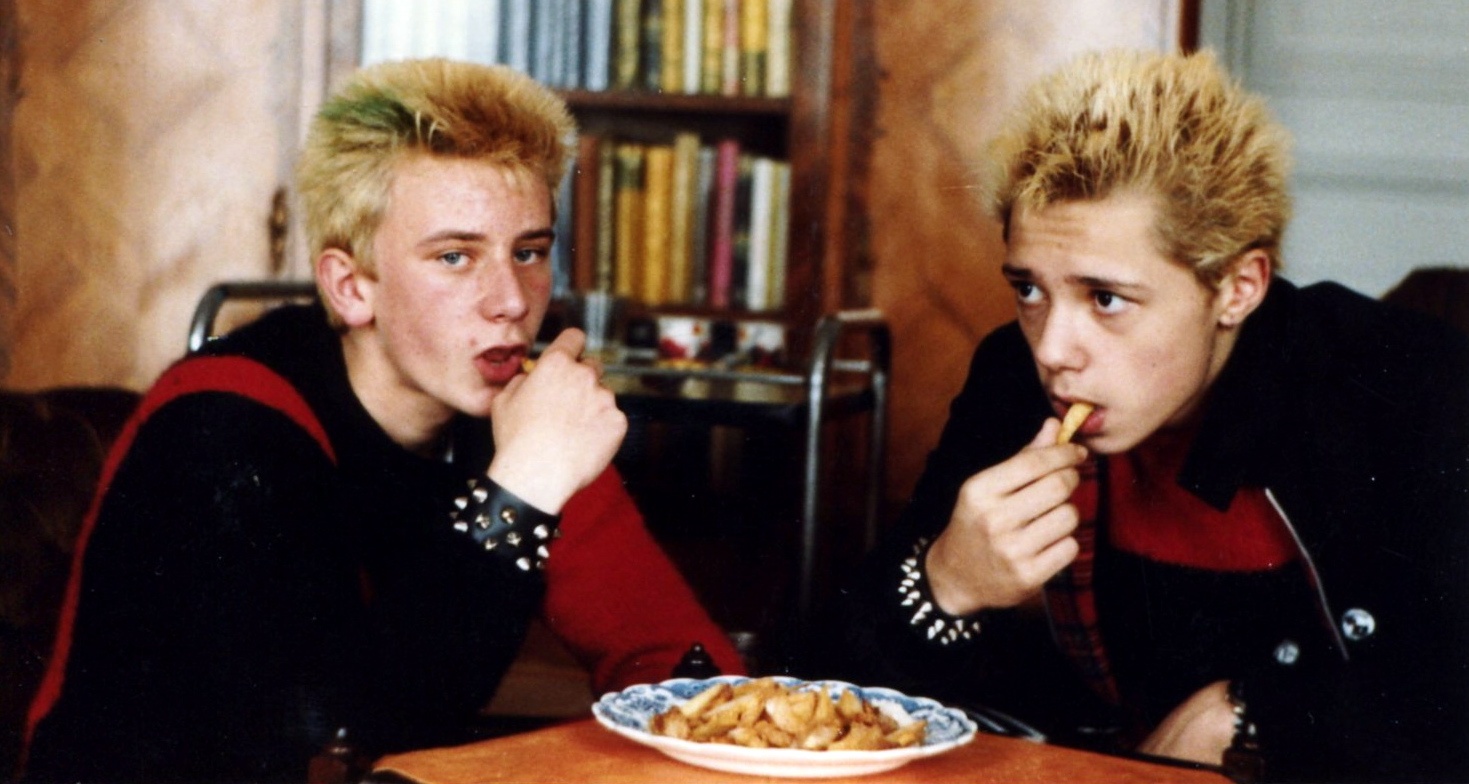

If difference in food habits created social exclusion from a group, the opposite - that shared food habits enforced friendships - is also true. As Deborah Lupton puts it ‘the sharing of food is a vital part of kinship and friendship networks’, and ‘the extent to which an individual is invited to share food with another individual is a sign of how close a friend or relative that person is deemed to be’. John from Bolton, like many in the survey, remembers eating the ‘scraps’ from the chip shop, bits of batter left over in the fryer as a by-product of frying fish, which were often given away free or for a few pennies. As his statement suggests, play through food also enforced friendships: ‘any unwanted chips could always be used to throw at friends’. A scene of a group of teenagers in school uniform sharing a chip-shop meal served in takeaway polystyrene packaging around the table evokes friendship and joviality.

As this image - showing chips, burgers, and fizzy drinks - also makes clear, the boundaries between traditional fish and chip shops and other cheap takeaway restaurants became increasingly blurred over the last part of the twentieth century. One important development in the history of the fish and chip shop was the ‘Chinese chippy’. After an influx of immigration in the late 1950s and 60s, Chinese entrepreneurs - especially in the north of England - started selling Chinese fast food alongside fish and chips. David recalls eating ‘half rice and half chips in curry sauce or sweet and sour sauce from a Chinese takeaway’ (or ‘half “n” half’ as Norman from Cardiff called it) walking home from social activities like youth club visits or ‘illicit visits to the pub in later years’. Judith from Leicester also remembered curry chips after nights out in town as an older teenager. As these memories also suggest, chips from these various fast food outlets often played an important part in social rituals involving drinking, at nights out at the pub or club. In these settings - when for many teenagers drinking alcohol was technically illegal or recently discovered by those at university - chips again took centre stage as a sign of youthful rebellion and friendship.

FAST-FOOD VANS & STALLS

“I remember burger vans mainly from the fairground, along with toffee apple/candyfloss stalls and chestnut stands. The best fast food available, mainly from the fair, had to be black peas with lots of vinegar.” John - Bolton, 1970s

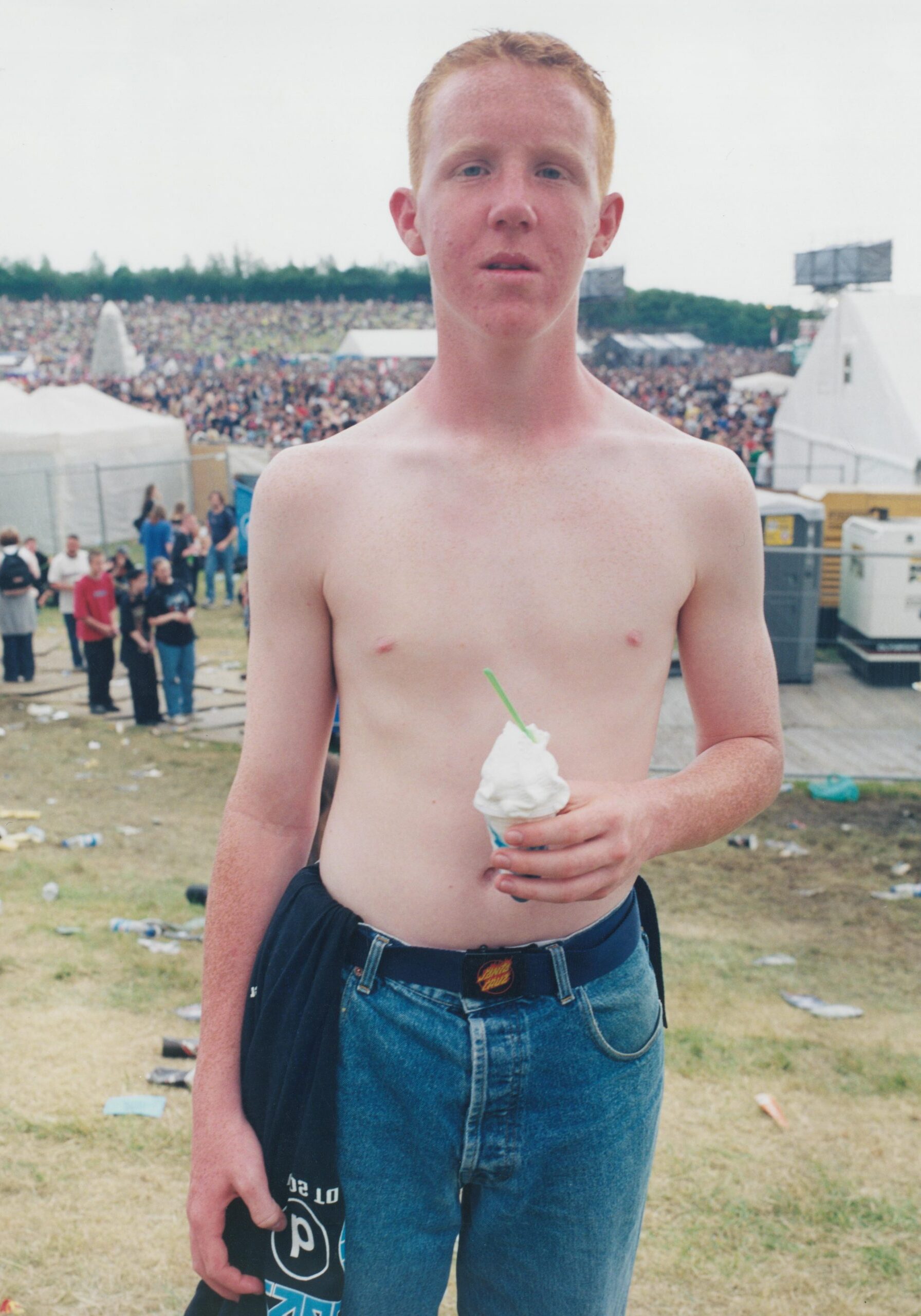

Paired with chips, kebabs or burgers could be consumed by young people after a night out with friends. Data from the National Food Survey from 1997 to 1999 shows that age impacted on the choice of foods eaten out, with a taste for burgers and kebabs meaning that those aged 15 to 24 consumed the highest amount of meat and meat products, as well as soft drinks and confectionery. Fast food like this from vans and stalls also appears in the Museum of Youth Culture’s archives at more specific celebratory social events, like university balls, fairgrounds, and football matches. Burgers served in cheap white-bread buns are eaten by undergraduate students at the Glamorgan University Ball in Rob Watkins’ photograph taken in May 1999; two young men eat jerk chicken and rice from a food stall at Nottingham Hill Carnival in the 1980s; a pair of friends dig in to hot doughnuts at Funland fair in the 2000s; and Manchester United football fans embrace at a match in Tony David’s photograph from 1990, framed by vans selling beans, peas, coffee, sausage, and chips. James a teenager in 1990s, also remembers a burger van outside Villa Park on match days in Birmingham. Music festivals, too, were an opportunity for unabashed fast food consumption. Catherine, who was by then at university, went to Reading festival in 1999 with a few friends, and remembers almost living off ice cream from the Baskin Robbins van, along with ciders!

Young women enjoying fast food at Glamorgan University Ball, Treforest, Wales, May 1999 by Rob Watkins | Two people eating jerk chicken and rice, at a food stall, Notting Hill Carnival, London, 1983 by Peter Anderson | Manchester United fans at the Wembley Cup Final, with fast food vans in the background, London, UK, 1990 by Tony Davis | Catherine and her friends eating ice cream at Reading Festival 1999, submitted by Catherine

However, Liam Bailey’s photo from Glastonbury Festival in 1994 hints at a counter-food-culture of wholefoods and vegetarian fast food. Behind a punk with a spiked mohican, two people are served at a fast-food van called ‘Hamsters Wholefoods’, notably selling vegetarian pizzas, pasties, salads, and cakes. Since the 1980s, the British anarcho-punk scene has played an important part in the vegetarian movement, with bands like Conflict producing rallying songs like ‘Meat Means Murder’ (1983), and joining in animal rights activism. The concept of wholefoods, meanwhile, only entered mainstream consciousness in the 1970s, in response to fast-food culture, in the wake of the arrival of frozen foods, artificial flavours, and processing technologies. It was pioneered by the American-born brothers and entrepreneurs Craig and Gregory Sams, and the latter actually provided the first macrobiotic (meaning, a diet focused on wholegrain, fruits and vegetables, and bean products) catering at Glastonbury 1971. Youthful consumers, then, also fed a growing market for health-conscious fast-food.

FAST FOOD CHAINS

“There was a McDonalds in Newport (the island’s major town) which was a must during shopping trips, and also a hang-out spot; me and my friends used to go there after the cinema on Saturday nights. I also had a joint birthday party there in the late 80s; we sat on plastic mushrooms and had a tour of the kitchen.” James - Isle of Wight, 1990s

When McDonald’s arrived in the UK in the 1970s, and for many into the 1980s and 1990s, it was a rare and rather exotic treat. Lola, a teenager in the Home Counties in the 1980s, remembers ‘queueing in McDonalds as it was such a novelty when it opened’. Gary, who also remembers being taken by friends to visit McDonald’s when it opened up in Cheltenham in the 80s, wrote that it ‘was the most disgusting thing I’d ever eaten’, and Ruth from the Isle of Wight remembers her first experience of a cheeseburger in the early 80s: ‘I was so disappointed that it contained meat and that it wasn’t just a lump of cheese’! Survey participants were on the whole more familiar with Wimpy (founded in the USA in 1934, and established in the UK in 1954), which notably had knives and forks and was more of an ‘eat-in’ restaurant. Moreover, in the 1970s those in Wales and bordering English towns may remember the National Milk Bar chain, where teenagers came to socialise over American-style milkshakes and ice cream sundaes in trendy surroundings, including bar stools and jukeboxes. The survey shows that many peoples’ memories of McDonald’s similarly focus on consuming milkshakes with friends, and it too became a youth-dominated space. For example, Matt, who grew up as a teenager in a rural Wiltshire village in the 1980s, describes McDonald’s as a hangout spot for his friends on nights out: ‘rather well-behaved provincial boys who thought shouting made up words in public was so funny that a thick shake would jet out of your friend’s nose’!

Fast food chains could also act as the perfect location for teenage romance. Jen’s enduring memory of her boyfriend was ‘drinking milkshakes in McDonald’s (strawberry, occasionally vanilla, but *never* chocolate)’! Karen’s first experience of McDonalds was a date, when she ordered ‘the cheapest thing on the menu- 59p hamburger’, and Judy, in 1970’s Stafford similarly remembers going to Wimpy with her first boyfriend from age 15-17.

Fast food restaurants have also traditionally acted as places of youth employment, a role that is often overlooked in social discourse. Owen, growing up in London Westminster and Richmond in the late 1980s, started working in the American burger chain Wendy’s (which for trademark reasons was actually initially called ‘Wendy’ when it opened restaurants in London in the 80s) at 15 years old. He remembers lots of their customers being those ‘200 to 300’ young people all trying to get served in the pubs on Friday and Saturday nights! An enduring memory is the smell of his clothes after each shift, burgers, fries and grease: ‘Your shoes would slide slightly until the pavement cleaned them’.

The rise of fast food chains in the UK was clearly tied to their role in teenage lives as places of socialisation and economic activity. As Annechen Bahr Bugge noted, these establishments were symbolically marked off from adult spaces, and ‘emblematic of this youth culture’. Nevertheless, as criticisms of fast food culture grew from the 1970s, fast food chains - and McDonald’s in particular - faced several challenges in the 1980s and 90s. For instance, the BSE or Mad Cow Disease scare in the British beef industry (especially in 1996) led many to switch to McDonald’s chicken McNuggets (first launched in 1983). Most notably, the so-called ‘McLibel case’ began in 1990 after members of London Greenpeace distributed a leaflet accusing McDonald’s of cruelty to animals, worker exploitation, damaging the environment, and promoting an unhealthy diet. Victoria, a teenager in Hull in the 1990s remembers having given up her occasional treat after her paper round of ‘6 Chicken McNuggets and chips’: ‘that stopped when I read about how they treated their livestock’. In mid-90s Bristol, Georgina remembers the impact of the McLibel press: ‘there were posters at the bus stop outside my school! My friends and I never went to McDonalds or any such fast food chains and we thought they were evil - I was a vegetarian anyway so wasn’t much point, we objected in grounds of principle to fast food’. Catherine in Kingston upon Thames also went vegetarian by the time she was a late teen in the 1990s, and remembers her brother putting anti-capitalist stickers on branches of McDonald’s to protest. Some young people joined in pressure groups that sought to force fast food chains to become healthier and more ethical. McDonald’s introduced bags of fresh fruit as an option instead of chips in the Happy Meal menus in 2002, and continues to face criticisms that emerged with most vigour in the 1990s.

INDIAN & CHINESE TAKEAWAYS

“My first Chinese takeaway was aged 15 - we decided to try it instead of the Saturday fish and chips. Hadn’t a clue what to order, so had stewed mushrooms - it wasn’t a great experience. Didn’t have Chinese takeaway again till I was 19, and then it became more of a regular thing. Though only ever had prawn curry and chips - my then boyfriend suggested it, I was still clueless, and I was still wary of rice! Rice wasn’t something we ate when growing up at all (except pudding rice which I hated!)” Karen - Birmingham, 1980s/ 90s.

By the end of the 1960s, there were 4,000 Chinese and 2,000 Indian catering businesses in Britain. Often serving informal, cheap food, and open late hours, they appealed to students and young people. As Nicola Humble claims, the rise of the high street Indian restaurant facilitated, in part by a population of students and young single people: ‘The success of Indian restaurants in the 1960s and 1970s was very largely the result of their appeal to a generation of young people living away from home for the first time: students benefiting from the massive expansion of the universities in the late 1960s, and the bedsit dwellers in the big cities’. According to the National Food Survey, as late as 1997 people aged 15 to 24 were the biggest consumers of these ‘ethnic meals’, at 66g per person per week, compared to the average of 38g across all age groups. Many survey participants noted the novelty of Chinese and Indian food, often indeed first encountering it when they left home for the first time. Simon, for instance, was a teenager in the 1990s, and says ‘I did not try a curry till attending university in the midlands, nor Chinese food... Only later, returning from university, did I introduce my father to curries, which he now much enjoys’.

These first encounters with Chinese and Indian food are memorable for many. Karen described not having ‘a clue what to order’ at a Chinese takeaway, and so ended up trying stewed mushrooms. Jo, too, a teenager in the 1980s in Stockport, wrote ‘always had mushroom curry which isn't really a Chinese meal at all! I had no idea. Half rice, half chips’. As Jo suggests, although these cuisines were new to many in Britain, they were adapted to British palates rather than being entirely authentic to their country of origin. Indeed, as we have seen, most Chinese and Indian takeaways could be served with chips. Both Chinese and Indian restaurants actually existed before WWI in Britain. Chinese food merged with Western tastes in the later part of the twentieth century as Chinese migration expanded in the late 1950s and early 1960s. A more distinctive ‘Anglo-Indian’ cuisine was brought over to Britain by the Victorian period from those who had lived in the Raj, but was developed by migrant entrepreneurs in the 1980s. It was their youthful customers who developed a taste for these evolving cuisines.

ICE CREAM

“Ice cream vans came to our village, and although I was more excited by them younger than 14, I’m sure the teenage me still loved an Oyster from Verrichia’s van blasting out Greensleeves down the estate.” Matt - Wiltshire, 1980s.

If Chinese and Indian food felt new and adventurous, ice cream felt familiar and comforting. Indeed, for many of us, the high-pitch jingle of Greensleeves evokes nostalgia for carefree summer days of childhood when sticky fingers would drip with ice cream. In the 1970s there were over 25,000 ice cream vans in the UK, compared to roughly 4,500 today. A particular favourite was the soft ice cream of Mr. Whippy, first sold from British ice cream vans in the late 1950s, and dubbed a ‘99’ when a chocolate Flake was added. Perhaps, like Ruth who grew up in North Yorkshire in the 1970s, you would ask for yours to be drizzled in ‘monkey juice’, meaning a sweet raspberry sauce. The 1999 National Food Survey confirms that the biggest consumers of ice creams (along with desserts and cakes) were children aged 5 to 14.

Yet, fast food from ice cream vans also played an important part in teenage youth culture. Jen, who was a teenager in Bradford in the 1990s recalls an ice cream van in the playground at school, where she remembers buying ‘chocolate rather than ice cream’. This reflects my own experience of lunch breaks in a Bristol secondary school in the mid-noughties, where the ice cream van and all its sugary treats were an important part of lunchtime fun amongst friends, something that seems scandalous by modern standards of public health.

Images from the Museum of Youth Culture highlight the continued association of ice cream with fun, innocence, and nostalgia among young adults. Rebecca Lewis’ photo shows a group of mods in the 90s eating 99 ice creams from a traditional ice cream van as they pose next to their scooters, a style both of fashion and of eating reminiscent of the 1960s. In another photo a man playfully spreads ice cream on a woman’s underarm whilst partying at Notting Hill Carnival in the mid 80s. In another, a sunburnt youth looks set to cool down with an ice cream after partying at the heavy metal Ozzfest festival of 2001.

“My parents were ridiculously conservative about food, preferring British food like chips, steak, roast chicken etc and looked down their noses at takeaways so I didn’t really have many until I earned my own money.” Tracey - Midlands, 1970s.

In a period of rapid change, new ways of eating, including the rise of fast food and the accompanying decline of the traditional family meal, were viewed by some as to blame for stereotypical youthful rebellions and the breakdown of social order. In the early 1970s, for example, Magnus Pyke wrote: ‘Teenage youths roam the streets [...] and magistrates complain that their parents exert too little influence over their behaviour. The marvel of food technology makes it unnecessary for them to go home for their meals’. Participants in the survey also continually looked back on a conflict between the expectations of their parents and the types of food consumption they were drawn to themselves as young people. Gerard, for instance, only experimented with new foods when he left his family home to go to university in the late 1970s as his parents were suspicious of new or ‘foreign’ eateries like the increasingly-popular Indian and Chinese restaurants. Many remembered their parents’ disapproval of the concept of eating in the streets rather than at a table, with Jane in the 70s even having to sit on a park bench to eat ice cream bought from the ice-cream van!

The stories presented here, however, complicate this negative narrative of gastronomic and cultural change, with fast food emerging as central in tales of youthful fun and friendship. It provided the social glue for first dates, after school meet-ups among mates, and drunken nights out. As such, fast food establishments were often marked as distinctly young spaces, which played an important role in young people’s social and economic lives. All the while, many youths still lead in criticising the broader ethical, nutritional, and environmental impacts of the fast food industry. Fast food consumption was also hugely varied. As we have seen, some foods, like the ’99 flake and fish and chips, enjoyed enduring popularity, reminiscent of tradition, childhood, and a constructed notion of ‘Britishness’. Others - like curry chips, McDonald’s milkshakes, and Indian takeaway - offered new flavours and novel ways of eating in a rapidly globalising Britain, that appealed to a sense of teenage rebellion and adventure.

Eleanor Barnett is a cultural historian of food, with a PhD from the University of Cambridge. Her doctoral research focused on the relationship between food and religion in the English and Italian Reformations. As @historyeats on Instagram, she posts more widely on food history, with fun daily facts, paintings, and recipes from across the world.

Commissioned as part of a Research Internship Programme in collaboration with the Centre for the History of People Place & Community at the Institute of Historical Research. Supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund as part of Setting the Record Straight