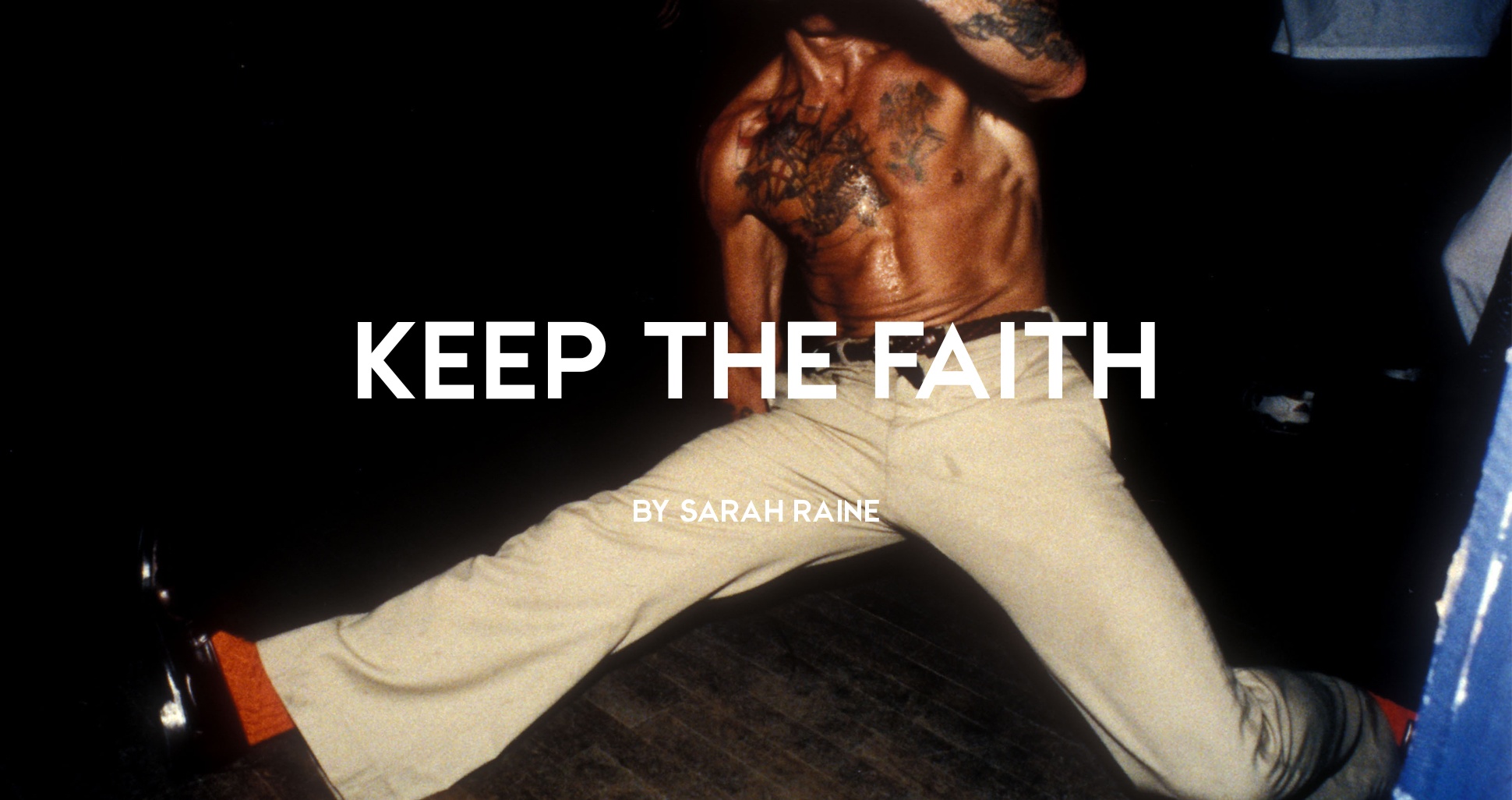

Keeping the Faith they say! American Soul found new roots in 60s North England as ‘Soulies’ came together for all-nighters at famous venues like the Wigan Casino. Dancing the night away in waist-flared trousers and doing acrobatics moves, Northern Soul quickly became a huge scene. Explore this passionate movements, its music and followers.

Text by Sarah Raine, Cover Photo by Rebecca Lewis.

The term ‘northern soul’ refers to both a dance-focused music scene that developed in the UK and an associated canon of records that are played at events. Having reached a heyday of popularity in the mid-1970s, northern soul is now a music scene that has found new fans – known as ‘northern soulies’ – from across the world and from different generations. These newcomers are generally welcomed by a passionate and dedicated community of music lovers, but they are expected to engage respectfully and knowledgeably with the practices, people, places and music of the scene.

Northern soul emerged as a distinctive music scene in the early 1970s, and was referred to as such in specialist magazines such as Blues & Soul. Since then, its development and identity has become associated with particular venues in the north and Midlands of England during the 1970s such as the Twisted Wheel (closing in 1971, Manchester), the Golden Torch in Tunstall (1972-1973, Stoke on Trent), the Wigan Casino (1973-1981) and the Blackpool Mecca (1973-1979). These clubs, however, were part of a much wider historic network of smaller events and youth clubs that put on ‘northern soul’ nights.

The scene reached a peak of mainstream media attention in the late 1970s, but following the closure of Wigan Casino in 1981 the scene moved to smaller venues and out of the mainstream spotlight. The scene continued, if comparatively depleted in the number of attendees, and changed with the musical journeys of DJs, dancers and record collectors in their desire for ‘new sounds’. The 100 Club in London continued to run a northern soul allnighter (from 1981), and a number of popular events were set up across the country, such as allnighters at the Top of the World in Stafford (1982-1986) and the Empress Ballrooms in Blackburn (starting in 1987).

Northern soul is not a genre of music but rather a canon of 7-inch singles that have become associated with the scene. The inclusion of particular records under the label of northern soul is established through either a long history of being played at events (known as ‘Oldies’ or ‘Anthems’) or by a DJ ‘breaking’ a new record. Whilst ‘new’ to the scene, the vast majority of records played on the northern soul scene were produced in American during the 1960s and 70s. The mid to late 1960s is considered to be the golden era of soul music by members of the scene, and their production much mythologised as ‘rejects’ of soul record companies, ‘discovered’ by British northern soul record collectors in dusty warehouses. However, most northern soul ‘anthems’ were produced for an intended popular audience, contenders for the ‘Rhythm and Blues’ (segregated) African American pop music chart.

"These newcomers are generally welcomed by a passionate and dedicated community of music lovers, but they are expected to engage respectfully and knowledgeably with the practices, people, places and music of the scene."

Established records have earnt their place in the canon through their rarity – few were produced and some are now very valuable within collector circles – a beat that fits with the northern soul style of dancing, their popularity at events in the 1970s, and (for some) their association with particular venues, such as Wigan Casino. Equally, the inclusion of new records is validated through ‘the beat’, musicians or record labels associated with northern soul, 1960s release dates, and limited production of the record.

Northern soul events are now organised across the UK by members of the scene, taking place in venues to hire such as working mens’ clubs, town halls, leisure centres and pubs. A wooden dance floor is required for the sliding footwork that lies at the heart of northern soul dancing. Allnighters (9pm-6am), alldayers (midday to early evening) and soul nites (7pm-midnight) host a range of northern soul DJs, who share their collections of rare 7-inch singles with passionate dancers that fill the dance floor. The music and practices of northern soul is considered by its community to be separate and distinctive from the music and culture of the perceived ‘mainstream’. As such, public events are places dedicated to dancing and to the music, with drinks banned from the dance floor and dancers expected to respect the space of others moving around them.

Although vinyl remains the authentic medium for listening to music, social media and scene-focused websites have become an important way of expressing and developing one’s knowledge within the contemporary scene. Websites set up in the mid-2000s provide a central hub and a packed scene calendar for this international music community. Events are also advertised on Facebook and Facebook Groups are dedicated to the sharing of music, memories and discussion, with northern soulies keeping in touch online in-between events and across continents. For the UK in particular, mainstream films such as Elaine Constantine’s Northern Soul (2013) and Shimmy Marcus’ Soul Boy (2010) have inspired a young generation of newcomers who arrive at public events having already established friendship networks through Instagram and Facebook.

Sarah Raine is a Research Fellow at the Birmingham Centre for Media and Cultural Research. Having completed a PhD on the contemporary northern soul scene, she is now an AHRC Creative Economy Engagement Fellow, working in partnership with Cheltenham Jazz Festival. Sarah is a founding member and co-Manages Riffs, a journal run by the staff and students of the BCMCR. She is also the Review Editor for Popular Music History (Equinox Publishing).

This essay was curated by The Subcultures Network, which was formed in 2011 to facilitate research on youth cultures and social change, and commissioned as part of the National Lottery Heritage Funded project to build the online Museum of Youth Culture. Being developed by YOUTH CLUB, the Museum of Youth Culture is a new destination dedicated to celebrating 100 years of youth culture history through photographs, ephemera and stories.

The National Lottery Heritage Fund invests money to help people across the UK explore, enjoy and protect the heritage they care about - from the archaeology under our feet to the historic parks and buildings we love, from precious memories and collections to rare wildlife.

Tune In

It Really Hurts Me Girl, Carstairs, 1968

Tainted Love, Gloria Jones, 1964

The Trip, Dave Mitchell and the Screamers, 1968

Hold On, The OJs, 1968

Stick By Me Baby, The Salvadors, 1968

Turn On

Northern Soul, Elaine Constantine, 2014