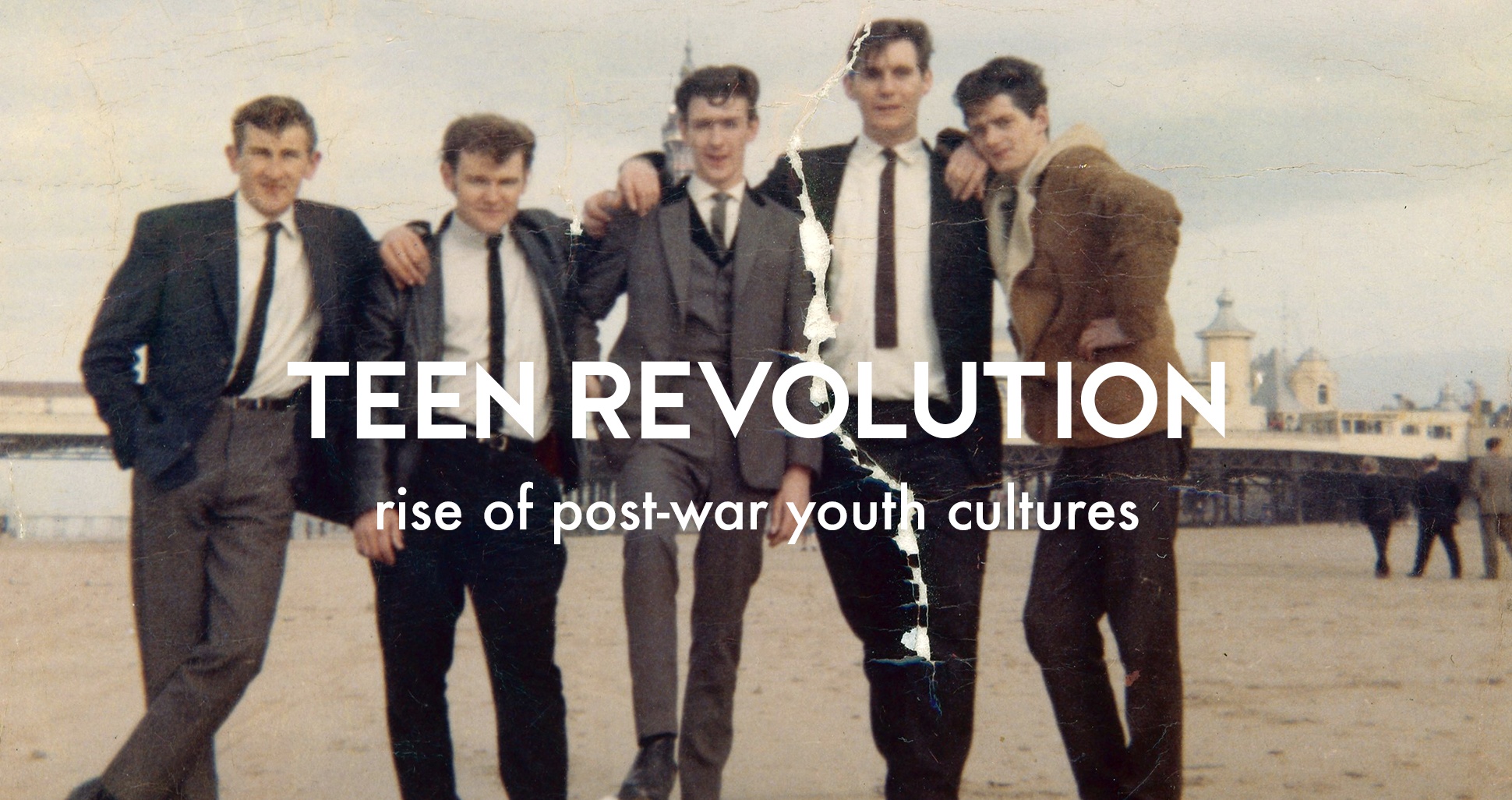

Youth Culture in Modern Britain Part Three: The Teenage Revolution.

Text by Bill Osgerby, Cover Photo Submitted by Bob Abraham.

In postwar Britain the explosion of the youth market was often treated as a benchmark of wider social change. The media, for example, could present youth culture in glowing terms, as an energetic and uplifting force displacing the dead hand of tradition. The Daily Mirror led the field, attempting to boost its circulation with enthusiastic coverage of pop music and, in 1957, even sponsoring a train (the 'Rock 'n' Roll Express') to take Bill Haley to London after the US rocker arrived in Southampton for his first British tour. More widely, an increasing association between youth and notions of social dynamism found its purest manifestation in the concept of the 'teenager'.

First coined by American market researchers during the 1940s, the term 'teenager' was imported into Britain during the early 1950s. Presented by the media and cultural commentators as the vanguard of contemporary social trends, 'teenagers' were configured as the sharp-end of a new consumer culture. As writer Peter Laurie contended in his survey of The Teenage Revolution, published in 1965, 'The distinctive fact about teenagers' behaviour is economic: they spend a lot of money on clothes, records, concerts, makeup, magazines: all things that give immediate pleasure and little lasting use'. In these terms, the phrase 'teenager' was not a simple description of a generational category. Instead, it also carried a wealth of connotations that configured young people as the precursors to a world of leisure-oriented consumption; an exciting foretaste of affluent good times soon to be within everyone's grasp.

Views of youth culture, however, were hardly unanimously positive. A recurring duality has always characterised popular debate about youth, with breathless celebrations of teenage consumption co-existing alongside fearful accounts in which juvenile delinquency and the commercial youth market are cast as depressing indices of Britain's decline. This litany of complaint has a long, connected history stretching back to the nineteenth century when anxious Victorians believed their streets were succumbing to a plague of violent 'hooligans' (a word that was, itself, a Victorian invention). Such perceptions have invariably been exaggerated and distorted, but have periodically taken root in the public consciousness through the machinations of calculating politicians and the hyperbole of a febrile press. Such moments of panic punctuated the 1950s and 1960s.

During the early 1950s specific anxiety cohered around the Teddy boy. Sometimes interpreted as a revival of Edwardian fashions, the Teddy boy's long, drape jacket was more precisely a British 'take' on American styles of the 1940s. First identified in London's working-class neighbourhoods in 1953, the Teds were presented by the press as the perpetrators of a 'new' wave of uniquely violent street crime. The scare-stories, however, were often inflated. Notions of a quantum leap in delinquency seemed borne out by rising crime figures, but − as is often the case − this 'juvenile crime wave' was largely a statistical phenomenon produced by new approaches to policing and changes in the collation of crime data. Indeed, rather than being a response to a genuine eruption of youth crime, the heightened fears are better seen as a symbolic focus for wider anxieties at a time of rapid and disorienting social change.

But delinquency and violence were not the only things that attracted postwar ire. Often, the very sartorial styles adopted by the young were viewed as a symptom of wider national decline. For many commentators of the time, America – the home of monopoly capitalism and modern consumerism – epitomised processes of cultural dissipation and, from this perspective, trends in youth culture embodied Britain's general drift towards a tawdry 'Americanisation'. Writers like Richard Hoggart, for instance, poured scorn on 'the juke box boys' with their 'drape suits, picture ties and American slouch', who spent their evenings in 'harshly lighted milk bars' putting 'copper after copper into the mechanical record player' – a realm of cultural experience that, Hoggart argued, represented 'a peculiarly thin and pallid form of dissipation'.

Such opinions, however, reek of snooty condescension. And, more importantly, they miss the powerful investment young people make in their style. In postwar Britain, for example, images of US popular culture seemed thrilling and romantic. Compared to the drab conventions of 1950s Britain, American style was exotic and exciting, and offered kids a seductive sense of individuality and worth. Indeed, it is exactly this sense of identity and empowerment that underpinned the succession of subcultural scenes that flourished through subsequent decades.

Bill Osgerby is an author and professor with a focus on modern American and British media and cultural history — with particular regard to the areas of gender, sexuality, youth culture, consumption, print media, popular television, film and music. Amongst other he has published, Youth in Britain Since 1945 and Biker: Style and Subculture on Hell’s Highway.

This essay was curated by The Subcultures Network, which was formed in 2011 to facilitate research on youth cultures and social change, and commissioned as part of the National Lottery Heritage Funded project to build the online Museum of Youth Culture. Being developed by YOUTH CLUB, the Museum of Youth Culture is a new destination dedicated to celebrating 100 years of youth culture history through photographs, ephemera and stories.

The National Lottery Heritage Fund invests money to help people across the UK explore, enjoy and protect the heritage they care about - from the archaeology under our feet to the historic parks and buildings we love, from precious memories and collections to rare wildlife.