When we think of Hip Hop we get drawn to America, but when this exciting music first cross the Atlantic in 1979 an incredible British homegrown movement formed, which can be traced to Grime and UK-Drill movements of today. Neil Kulkarni writes about the UK movers and shakers that made Hip Hop a British thing.

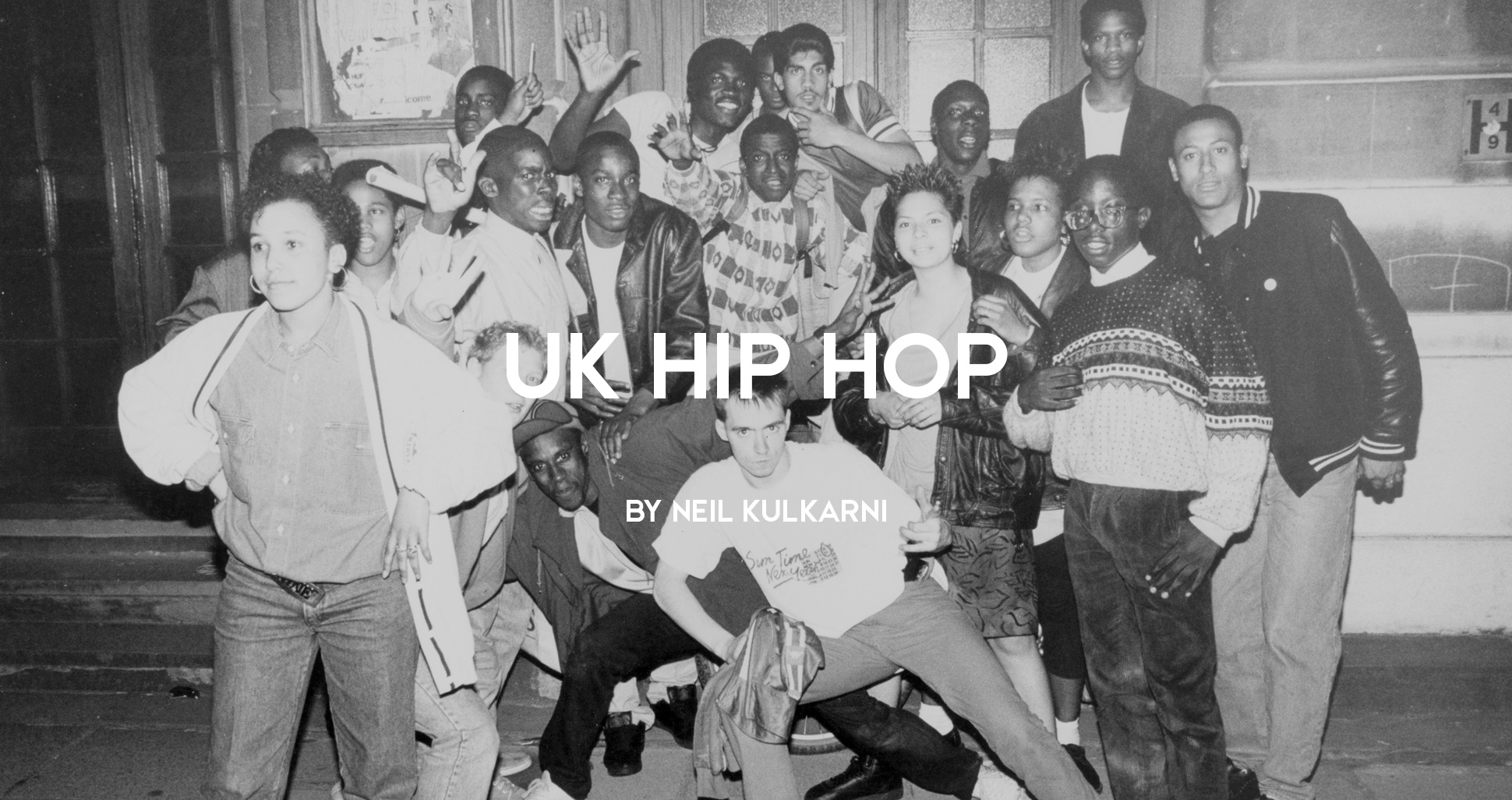

Text by Neil Kulkarni, Cover Photo by Normski.

When hip hop exploded out of the New York boros in the mid-70s it touched down worldwide and transformed into new forms – the UK fell in love with rap music instantly and immediately started fracturing and bending its impact into new shapes, blending in uniquely British influences to create a music scene that was uniquely British, and that has found itself mutated into genres like jungle, breakbeat, drum’n’bass, grime and UK Drill.

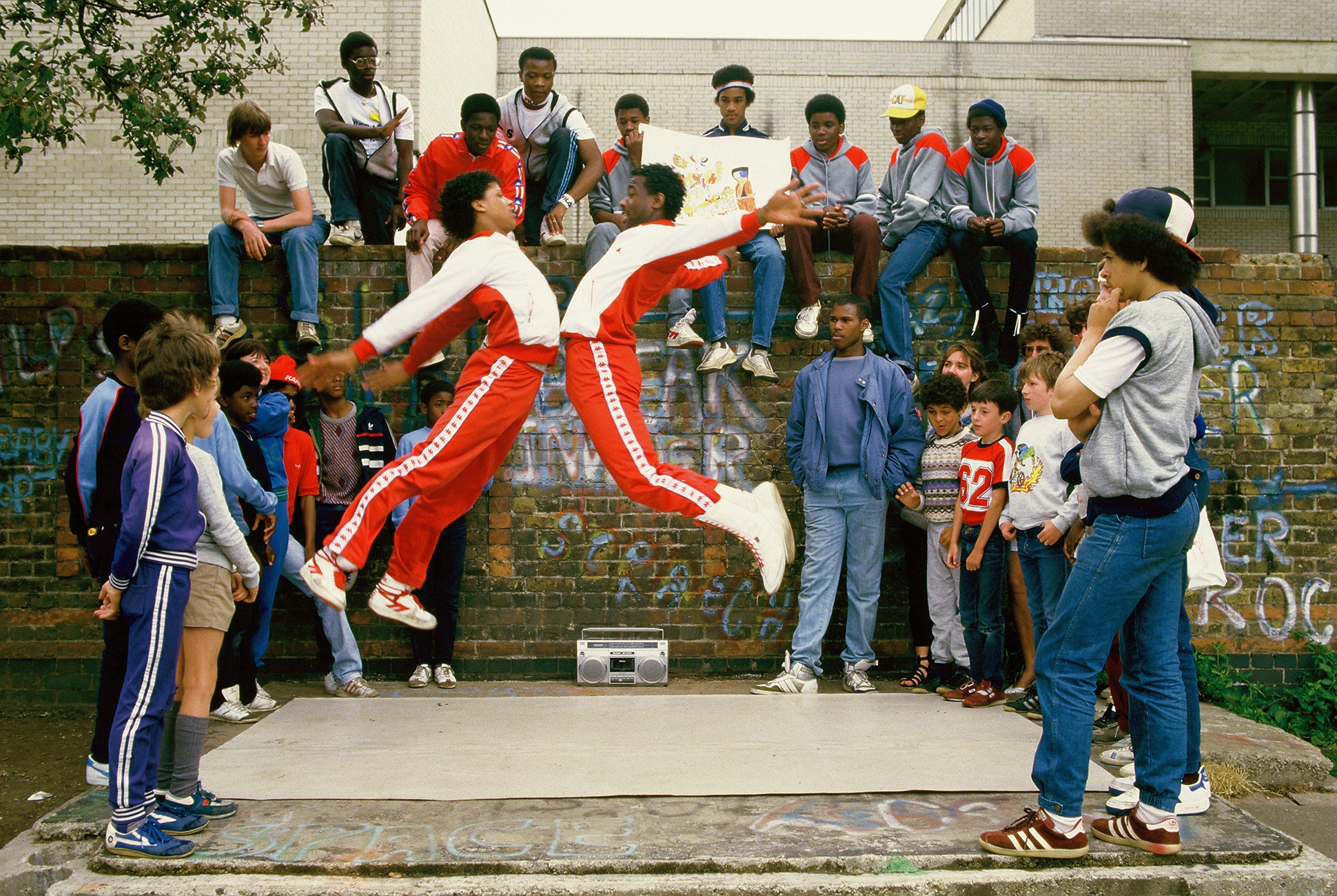

This is a story that’s still on-going but for the UK, the hip hop story starts with the release of Sugarhill Gang’s ‘Rapper’s Delight’ in 1979 – crashing into the UK Charts at number 3 it introduced a whole generation of future UK-rap fans to this new form of music. For many in the UK’s black and Asian communities hip hop carried a dual sense of purpose and strength – its multiple musical influences, reggae, soul, blues, jazz, funk and spoken word gave hip hop a freedom that many fans were not finding in their own lives in Thatcherite Britain. Hip hop grew among the multicultural diasporic 2nd-generation youth of the big British cities, scenes starting up that are still producing fresh UK talent in London, Nottingham, Bristol, Birmingham and Manchester. From the off, hip hop in Britain was a cross-racial scene, united more by class than race because of the UK’s lack of racial segregation in its inner cities. UK rap has always been underdog music, the voice of those marginalised by mainstream culture. It took time for it to both find, and fight for, that unique voice.

"When the hip hop scene exploded, and what I would regard as early contemporary urban scene (the street style scene), it was coming of age. It was really vibrant and really positive and, politically, it was averse to have something that a lot of people could affiliate with. " - Normski, Hip Hop Photographer

Initially much of the UK rap scene was dependent on American imports of both records and tapes but also the clothes (Wranglers, Kangols, Fila), the breakdancing and the graffiti-styles that formed such important pillars of hip hop in the US. If UK musicians used rap it was often in slavish imitation of American archetypes, as an effect of pop (Adam & The Ants ‘Ant Rap’), or in novelty records like Morris Minor’s ‘Stutter Rap’. The growth of hard-core rap in the US with Run DMC and Def Jam records in the mid-80s gave UK rap the confidence to take the form back to its own streets and start telling its own stories in its own unique way. Fledgling pioneer British rappers and crews like Derek B, London Posse, the Cookie Crew and Monie Love, Sindecut, Demon Boyz, DJ Newtrament, and Ruthless Rap Assassins bought the pressures and tensions of the UK streets to the form of rap, often blending in a heavy reggae and dancehall influence from the soundsystem cultures of its mainly Afro-Caribbean audience. Rappers like Black Radical MKII took on the explosive lessons of Public Enemy and applied them ruthlessly to Britain’s own colonial history. As the 80s turned into the 90s, an increasing amount of British rappers started firmly rejecting any attempt by UK rap to mimic its US counterpart. This new scene, dubbed ‘Britcore’ included crews like Hijack, Gunshot and artists like Silver Bullet and Son Of Noise – their raucous music was a million miles away from the more polished productions emerging from the American west-coast at the time, and featured lightspeed-fast rhyming heavily laced with Jamaican patois and influenced by early UK soundsystem toasters like Papa Levi and the Saxon Sound crew.

The explosion in breakbeat and rave in the late 80s and early 90s was not only influenced by UK rap but actually took many of the original UK rap artists away into more dance-based (and lucrative) forms like jungle, trip-hop and drum’n’bass. As the 90s dawned hip hop in the UK found a sharper political edge – events like the Broadwater Farm riots gave many UK rappers a flashpoint to fire their angst with police and an overtly racist society. Crucially late 80s rap in the UK was so vibrant and so fast moving it finally found itself embedded as a culture with its own unique networks and self-sustaining spaces. UK rap finally had its own clubs – from its centre-point in Ladbroke Grove and Soho clubs like the Wag and the Limelight, as well as major events like the UK Fresh festival, the culture found itself cropping up in Bristol, Manchester, Nottingham, Leeds – anywhere, where disaffected youth in love with US hip hop wanted to hear a high-energy aggressive UK twist on the form. It had its own radio presence through pirate stations like Kiss and Rinse as well as DJs like Tim Westwood. It had its own dedicated record-shops like Mr Bongos. It had its own press with magazines like Hip Hop Connection and fanzines like Fat Lace. It finally was avoiding the temptations of major labels to create its own imprints like Music Of Life, Low Life, Kold Sweat, Vinyl Solution and Big Dada records. By the mid-90s, UK rap had firmly established itself as here to stay and the on-going explosion of artists, labels and scenes has continued to this day, exerting a huge influence on the grime and UK-drill scenes that now occupy that central space to young disaffected UK kids. By both interpreting and refuting the dictates of US hip hop, UK rap has found its own distinctive voice and unique sound.

Long may it rage.

Neil Kulkarni has been writing about hip hop music for a quarter of a century and is the author of 'The Periodic Table Of Hip Hop', 'Eastern Spring' and 'Bring The Noise: The Stories Behind Hip Hop's Biggest Songs’, as well as being the Hip Hop editor at DJ Magazine.

This essay was curated by The Subcultures Network, which was formed in 2011 to facilitate research on youth cultures and social change, and commissioned as part of the National Lottery Heritage Funded project to build the online Museum of Youth Culture. Being developed by YOUTH CLUB, the Museum of Youth Culture is a new destination dedicated to celebrating 100 years of youth culture history through photographs, ephemera and stories.

The National Lottery Heritage Fund invests money to help people across the UK explore, enjoy and protect the heritage they care about - from the archaeology under our feet to the historic parks and buildings we love, from precious memories and collections to rare wildlife.

Tune In

It's a Shame, Monie Love, 1991

Ripping Up The Industry, Black Radical MKII, 1990

20 Seconds to Comply, Silver Bullet, 1990

Females (Get On Up), Cookie Crew, 1987

How's Life In London, London Posse, 1990

Turn On

Wild Style, Charlie Ahearn, 1983

Beat Street, Stan Lathan, 1984