We like to think of the Teds as the first British youth culture movement, but also emerging around the same time were the hipsters and ravers of the 1950s. Inspired by the Beatniks of America, they roamed coffee shops and Jazz bars of London and beyond. Delve into this movement, from the music to the politics, for a different type of 50s youth culture.

Text by David Wilkinson, Cover Photo by Stephen Cassidy.

Just as the word ‘punk’ goes back at least three centuries and has variously meant ‘thuggish’, ‘worthless’ and ‘male homosexual’, so our present-day use of terms like ‘hipster’ and ‘raver’ have evolved somewhat from the meanings attached to them back in the 1950s.

Late ‘50s Britain wasn’t all Teds, Elvis and jukeboxes. In jazz and folk clubs up and down the land, a new style and set of values was stirring. Jazz brought together upper class rebels with the socially mobile but culturally displaced working and lower middle class. The novelist and journalist Colin MacInnes, whose work vividly documented the youth culture of the era, believed of this class mixing that ‘the kids just don’t seem to care about it at all’. A new age was dawning and these original ‘ravers’ heralded the emergence of youth as a metaphor for social change. Whilst they were far from ‘classless’, as the most optimistic commentators of the 1950s believed, there was little doubt that segregation and deference were breaking down under the influence of the welfare state and an expanding popular culture.

Jazz also brought together black and white youth as Britain became a multiracial society in the wake of postwar immigration from the Commonwealth. As with class, there was little utopian about this moment – the summer of 1958 was marred by a spike in racist assaults and it would be a full decade before the introduction of the Race Relations Act, which outlawed the refusal of work, housing and public services on the grounds of race – but youth culture at least provided a space in which those of different races and ethnicities might cross paths.

Young people’s attachment to folk, meanwhile, could be traced at least as far back as the 1930s, when figures like the Salford-born singer, playwright and Communist Ewan MacColl began to mine the rich oral traditions they’d grown up with, adapting and transforming them for the mid twentieth century. As with jazz and rock ‘n’ roll, though, the United States’ postwar cultural influence was felt in the world of folk. The craze for forming skiffle bands, a fusion of folk with US jazz and blues, may well have been the first instance of the ‘do it yourself’ ethic later so central to British youth culture. Washboards, broomsticks and tea chests became makeshift instruments and teen skiffle groups were often the origin of some of the most mythologised names of the 1960s, the Beatles amongst them.

"Young marchers ‘appeared from nowhere in their grime and tatters, with their slogan-daubed crazy hats and streaming filthy hair, hammering their banjos…It was this wild public festival spirit that spread the CND symbol through the jazz clubs and secondary schools…Protest was associated with festivity."

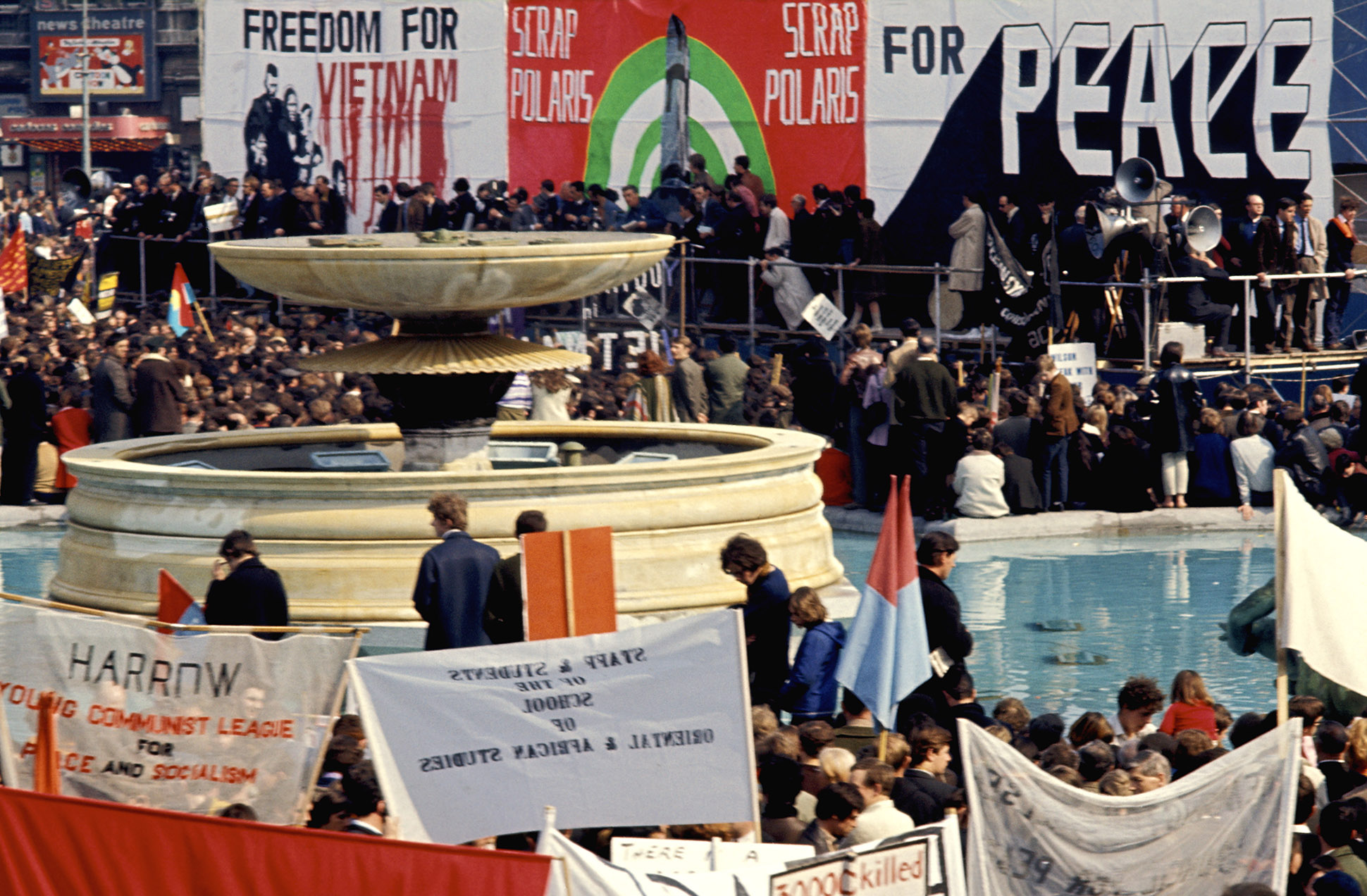

Music may have been the focus at these clubs – but it wasn’t all that was on young people’s minds. Months after The Daily Express announced ‘It’s Our H-Bomb!’ of Britain’s recently acquired nuclear deterrent, the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament was launched in February 1958. Formed by high-profile intellectuals, politicians and cultural figures, it rapidly grew into a youthful mass movement as the very real threat of armageddon acted as an existential lighting rod for a range of discontents. At the height of CND’s influence a few years later, marches attracted around 150,000 and the movement succeeded in securing a short-lived policy commitment from the Labour Party to unilateral disarmament.

The poet, artist and jazz musician Jeff Nuttall recalled CND marches as ‘carnival[s] of optimism.’ Young marchers ‘appeared from nowhere in their grime and tatters, with their slogan-daubed crazy hats and streaming filthy hair, hammering their banjos…It was this wild public festival spirit that spread the CND symbol through the jazz clubs and secondary schools…Protest was associated with festivity.’ That potent fusion of desire and dissidence helped lay the foundations for the enduring association of youth culture and popular music with political opposition, feeding most obviously into the counterculture and student movements of the 1960s.

In the words of historian Raph Samuel, a further ‘nursery of 1960s counterculture’ was the recently established New Left. A loose milieu of socialists united in their opposition to the compromises of the Labour Party and the repression of the Soviet Union, their frequently bohemian meeting places like the Partisan Coffee House in Soho overlapped with and informed the nascent subculture around CND. Its clientele featured everyone from Doris Lessing to Quentin Crisp. Playwright Arnold Wesker secured trade union funding for a venture called Centre 42, which toured the regions for working class and regional cultural talent like Anne Briggs, who left her East Midlands home at 15 to become a folk singer.

This melding of high seriousness with popular cultural exuberance was also apparent in the popularity of poetry. No longer the preserve of the privileged metropolitan or the sensitive young man, literate hipsters of different classes and genders began to appear. They were inspired by a network of DIY ‘little magazines’ featuring the work of US Beats like Allen Ginsberg. These helped liberate poetry from its confinement to elite universities or London-based publishers as scenes cropped up in bookshops and pubs everywhere from Blackburn to Nottingham. Freewheeling verse met European existentialist philosophy as all-black outfits joined duffel coats and hash smoke, with young people looking beyond national borders for new ideas. Such productive fusions of art, theory and pop have generated successive waves of youth culture ever since.

It was not necessary to leave Britain for a taste of freedom. Like their US counterparts, some beatniks took to the road, appearing in unlikely spots such as the beaches of Cornwall. Broadcaster Alan Whicker reported on this phenomenon for the hugely popular BBC programme Whicker’s World in 1960. Wryly noting that even a ratio of one beatnik to every thousand of Newquay’s population was too much for the town’s ‘burghers’, he describes how the local council and businesses attempted to drive out these unwelcome visitors. The footage is an early example of that media feedback loop in which the exposure of the apparently outrageous transgressions of the young only ends up contributing to their popularity.

David Wilkinson is a lecturer at Manchester Metropolitan University, specialising in the area of popular musical and subcultural studies, and considering countercultural legacies in Britain.

This essay was curated by The Subcultures Network, which was formed in 2011 to facilitate research on youth cultures and social change, and commissioned as part of the National Lottery Heritage Funded project to build the online Museum of Youth Culture. Being developed by YOUTH CLUB, the Museum of Youth Culture is a new destination dedicated to celebrating 100 years of youth culture history through photographs, ephemera and stories.

The National Lottery Heritage Fund invests money to help people across the UK explore, enjoy and protect the heritage they care about - from the archaeology under our feet to the historic parks and buildings we love, from precious memories and collections to rare wildlife.

Tune In

A Night in Tunisia, Charlie Parker, and Dizzy Gillespie, 1951

Quick Silver, Horace Silver and Art Blakey, 1959

Cubano Chant, Art Blakey, 1957

Spinning Wheel, Delia Murphy, 1939

Dust Bowl Ballads, Woody Guthrie, 1940

Turn On

Bird, Clint Eastwood, 1988

Expresso Bongo, Val Guest, 1959

Pull my Daisy, Robert Frank, 1959